|

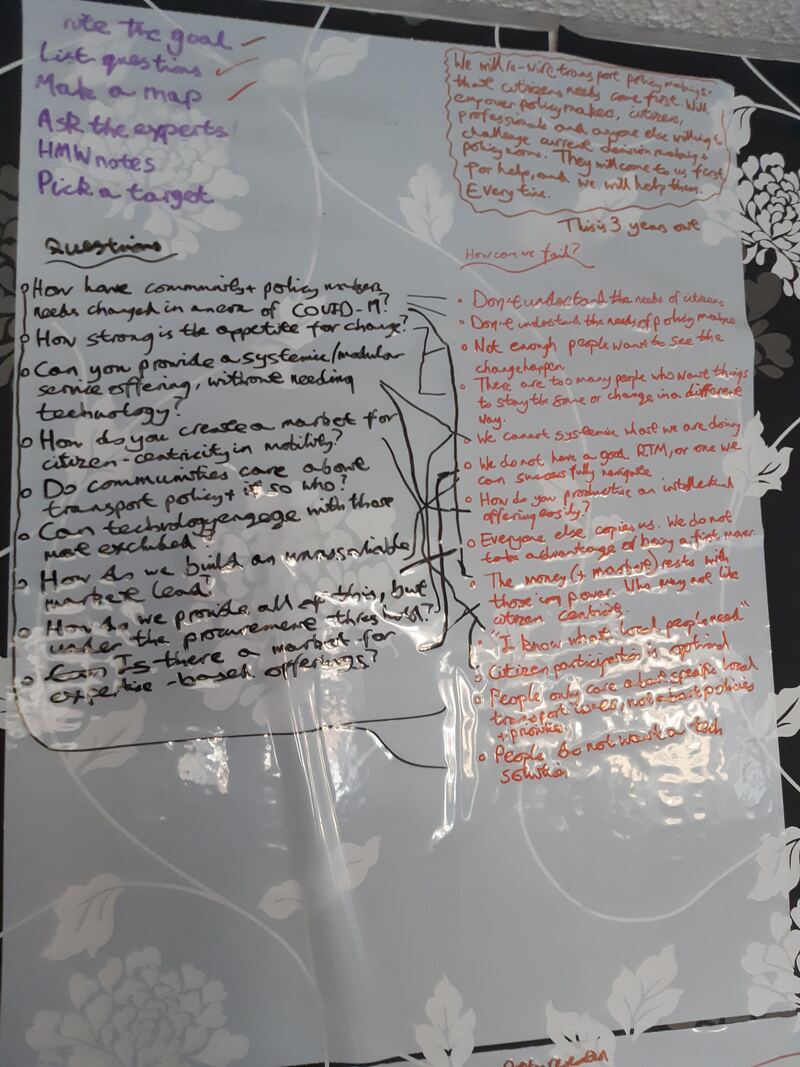

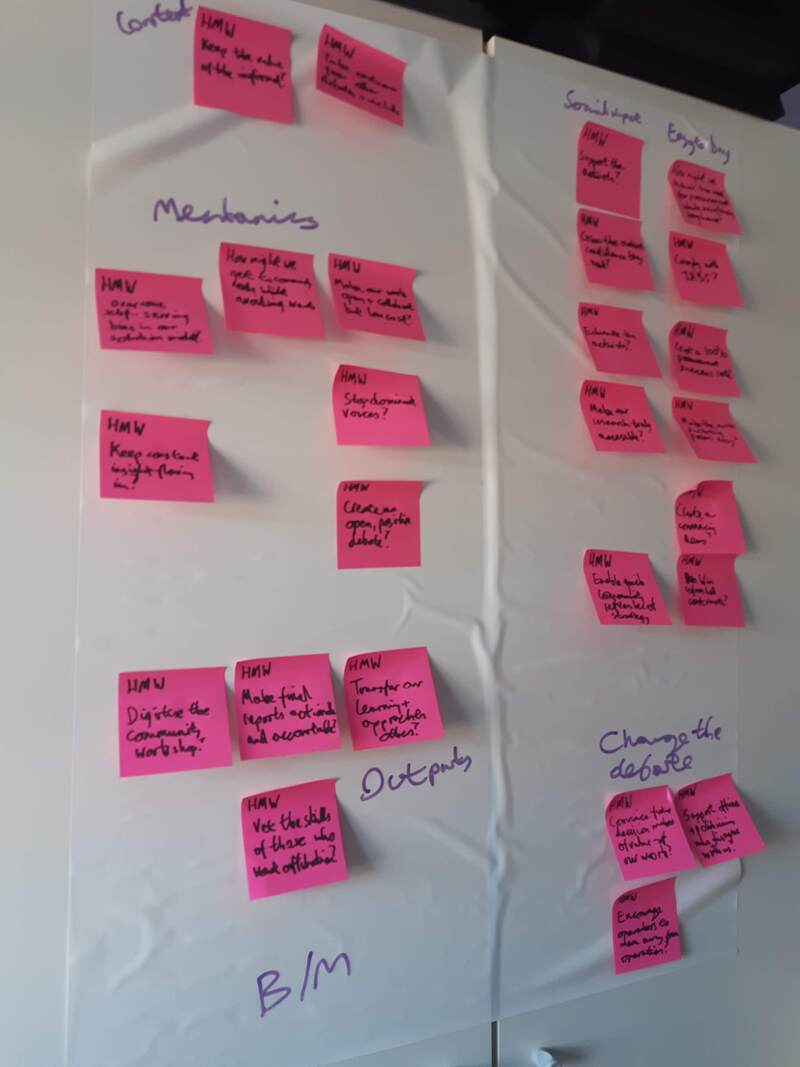

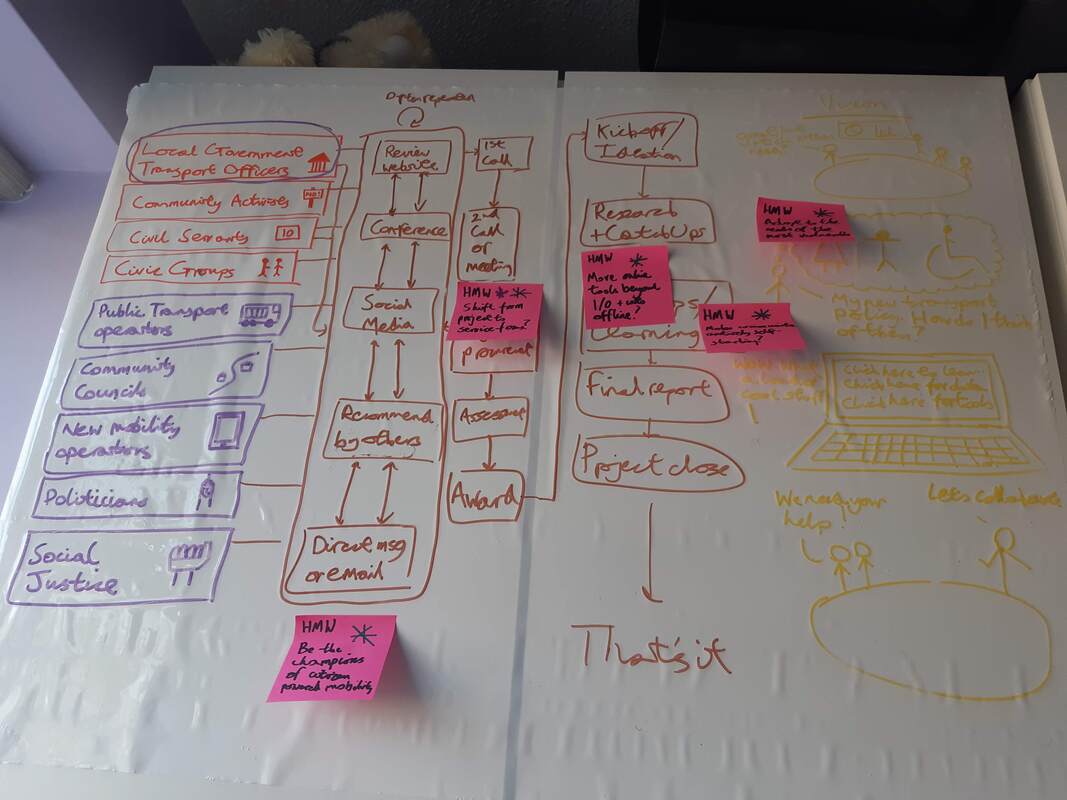

If you want to skip the background, and straight to the end, we want to talk to transport planners and activists this coming Wednesday about a service we are developing. Links to book a time are at the end of this post. Before we start - how are you? I hope that you are keeping safe and well during this turbulent time. I hope that your family, friends, and communities are keeping well, and that you feel supported. For us, we feel like we are in the eye of a hurricane. The chaos is raging, and it is within touching distance. But there is a strange calmness that belies the danger all around. But we are using this calm to do and think anew. You may have already seen our international research project New Normal? and the work we are doing to support the Transport Planning Society. In this post, I am calling for your help in reshaping what Mobility Lab will look like. We need it, quickly. I mentioned in a previous post how we were planning to accelerate our tech development. We kick started this process last week, and very early on came to realise that our original plans were great...for when we originally came up with them. Our entire context had shifted, and so our plans needed a big shift as well. So I started off a business design sprint. Reviewing our current processes, and our original plans, and mapping out how they work, and whether they still apply in this new world. Here's a clue: they didn't. Well, kind of didn't. Whilst the processes that many of our potential customers go through is still the same, the feedback that we got was that process on community engagement and transport was being overtaken by events. I chose a sprint as the most appropriate method for two reasons, both related to the fact that time is of the essence. Firstly, we want to shift away from our current consultancy focus as this is not applicable in a time when the need for doing good things is great, and finances are stretched. Secondly, there are opportunities for government support to help us create something of immense social value, whilst shifting our operational model, but they close very soon. So what are we looking to build? Well, I am still in the process of the sprint right now. But the key conclusions that we have identified so far are as follows:

This, in a sense, is the problem statement. Previously. an online engagement platform was a very much a digital tool for an analogue age. Whatever the solution is, it needs to be a digitally-analogue tool for a digitally-analogue age. When I mapped our current service offering, and how we might make significant improvements, it was clear that a shift in the operational model is essential if we are to answer many of the questions posed in this new reality. Now, I need your help.

If you are a city or local authority transport planner, or you are an activist, I need to talk to you. All I need is 30 minutes of your time to run the solution idea past you. It is essentially a sense check on what we are proposing, and how we could make it better. What do you get from it? Is a good feeling not enough :)? In all seriousness, when we develop the final solution, we will give you a discount. On this coming Wednesday (15th April 2020) we are offering the below 30 minute slots for a chat. All you have to do is book them. 12 - 12:30pm - Book now 12:30pm - 1pm - Book now 1pm - 1:30pm - Book now 1:30pm - 2pm - Book now 2pm - 2:30pm - Book now 2:30pm - 3pm - Book now 3pm - 3:30pm - Book now 3:30pm - 4pm - Book now If you have any questions, you can just email us. Otherwise, we look forward to chatting to you.

0 Comments

We won't waste your time. No doubt your head is spinning with what has happened over the last week. So here is what we plan to do to help you through this all.

My, how a crisis focusses the mind. Our scenario planning training is going online From our discussions with good friends over the last week, what has been clear is that many need the tools to make good decisions, and now. So we are taking our popular Scenario Planning for Transport training online. We are currently restructuring the course so that participants can collaborate much more easily. Not only are we looking at tools which will allow remote collaboration, but we will also be more flexible on how it is delivered. For example, as opposed to having to dedicate two whole days to training, we will experiment with 4 half days over a couple of months. You can get an idea of the topics we will be covering on the course page. The course will be delivered by Zoom, Skype, Hangouts, or whichever conference calling system you have. We are able to offer the course to all time zones, so even if you are on the other side of world, we can help. We will be offering online courses from 1st April, but we are open for bookings now. If you are interested, then email us. Rapid-fire trend analysis for a changing world We regularly get asked what are the biggest trends in mobility and the civic space, giving our insights into what is happening. COVID-19 changed all that. Not only do people want this insight, they want it now, as they need to make a decision now. People's livelihoods are on the line here. All the while, traditional transport planning and strategy making in cities continues onward, but with already stretched officers having to muck in with keeping public services running. Or deal with the kids at home. So we are going to formalise this. We have done some work to set up a simple process where you can go from an initial inquiry to us producing a tailored trend report for you within a week. This is mainly aimed at city authorities who want to create citizen-centred mobility policies but are now struggling for resource to deliver it. But if citizen-centred mobility is your thing and you are a company or community group, it works just as well. You can find out more about how it works on our dedicated web page. We are charging for this, but if you are an NGO or community group there is a discount. We are not fussed how we present our findings to you - whether slide deck or through video conference. All that matters is that will help you keep the long view in mind. Things like climate change an inequality will still be here once this is all over. We are supplementing this by working hard on a free-to-use trend deck, based upon our horizon scanning work. This will be available in early April. If you want to get started, email us. Bringing out the post-Corona view We know that there are a million conversations taking place across mobility about what a post-Corona (PC?) world will look like. We are assisting in many of those conversations, and having our own of course. But these conversations need joining together to develop a collective view of different futures. We have started some conversations with many good people in Europe, the USA, and New Zealand about creating a huge online conversation on 'Mobility PC' (working title that we just came up with). We will be using open tools and innumerable conversations to collect the data and signals of change, and to collectively analyse to develop these future scenarios. Oh, and we will be doing it for free, and in the open. This will be a lightning quick task - from start to completion within 6 weeks, with a crazy amount of work in between where the only reward is the kudos. We need volunteers to help make it happen. People to host online chats, to provide their evidence, to crunch numbers, and to help analyse potentially reams of feedback. It's a big ask for exceptional times. But if you are up for it, then get in contact with us. We are accelerating our tech that will get communities engaged in strategy making We must admit that we have fallen behind on our initial plans to get a beta developed for our online engagement platform. But despite us having to keep 2 metres from one another, the demand for community engagement will not go away. We are already talking to local authorities about how we can engage communities in their scenario planning work. Delphi studies and facilitating online discussions is something that we can do for you (at a charge), but its not quite what we are after. So by early April, we will publish our plan. And within 6 weeks will will have an alpha of our solution published. In the meantime, we are working closely with Annette, German, and the brilliant team at Future Fox on their online community engagement tool for streets and placemaking. If you want to talk community engagement right away, contact them. Our whole world has shifted overnight. We are all working like crazy to make sense of it all, to support ourselves, and to support the most vulnerable. Suddenly the world has become a crazier and more frightening place.

We are trying to do our bit in all of this. From the big changes outline here to the lending a helping hand to those who live near us who truly need our help. All whilst keeping the long view and the needs of people in mind. We wish you all the best. Remember, we are here for you if you need us. We can give you tools, pause for thought, and give you a new way of thinking about the world. Or just a virtual cup of tea. Stay safe, and stay positive. If you haven't checked out Part 1, Part 2, or Part 3 of the history of Mobility Lab, then you should before reading on. An uncomfortable fact that you learn early in public engagement is that for most people, talking to the public is really hard. As social animals that comes as a bit of a shock. We are really good at establishing social circles, and co-operating has been critical to our survival. But engaging people in decisions is another matter. Throughout my life I have never been able to explain this. But once you realise it, you see it everywhere. The first time that I started seeing this was during the UK General Election of 2005. This was only my second as a registered voter. As a second year University student, my interest in my first election was non-existent. My second election made we wonder why we run them at all. I live in what is known in the UK as a safe seat. It has returned a Conservative MP in every election since 1932. The Conservative Party could put a pig with a blue tie up for the vote, and it would win. This is reflected in the nature of the political debate that takes place locally during the election. I have lived in this seat for five elections now, plus two referenda. In that time, I have seen one candidate canvassing for votes, and received a total of five leaflets through the door. At a time when there is meant to be a big debate taking place on the future of the nation, there is no invite to it. "But you have to educate yourself. It is your duty as a citizen to be informed before voting" more than one person has said to me. But if candidates cannot be bothered to put the effort in to secure my vote, why should I vote for them? When they clearly don't care about coming to get my vote? Over the years, the direction of my vote has been determined by a simple rule. If you have made the effort, I will think about voting for you. If you can't be bothered, I won't vote for you even if I like your policies. The same thing applies to public engagement. If you can't be bothered to make the effort to engage them, why should you expect more people to engage? You have no devine right to their attention. People should not expected to care about what you are doing, and how important it is to them. You should not expect people to educate themselves. If you don't make the effort, don't complain that others do not. This is partly why public engagement is done so badly most of the time. Good public engagement takes time and effort. Not to plan and to do. But to convince people that you care, and you are engaging on their terms. Trying to engage people on my terms is a mistake that I often made. Once a month for two years, I stood at a stand at Leighton Buzzard railway station trying to convince people to try out the bus or local cycle routes to the station. It went about as well as you would think. Most people ignore you. Then some take a leaflet just to get you off their back. Perhaps one or two thought about taking the bus. My failure to convince people I put down to not being there enough, and not puttng the hours in. I wasn't selling enough. I convinced myself it was a numbers game. Just talk to more people over more mornings and evenings. I was wrong. That revelation came one dark December evening in 2010. I was on my fifth shift promoting sustainable travel at the station of the week. It had been a quiet night, and I had been routinely ignored by exhausted commuters heading home after a long day at work. Then Claire (not her real name) walked in. As tired and as stressed as the rest of them. More out of hope than anything, I asked her whether she was interested in finding out about different options for getting to and from the station. "It would save the hassle of getting a taxi" I said as a throw away comment. "Ahh...why not?" she said in response. The next 30 minutes was not spent talking about buses, bikes, and detailed journey planning. But with Claire sharing with me her life. The job with the long hours, trying to balance a home life alongside this, and the sweet relief of the Americano served by the station cafe in the morning. The cafe owner may have been in earshot at that point. In part this seemed like therapy for her. I didn't mind, and not because it had been a slow night. Seeing the visible relief on her face at sharing her worries with someone was enough for me. Bus timetables and discounted fares suddenly lose their importance during times like that. I had completely forgotten that I had even given her a bike map. I wasn't sure if any of what I was doing was helping. There was little change in facial expression or demeanour, and all I was saying was "ok," "uh-huh," and "I understand" every few minutes. But we parted on good terms. Six months later, I was working Leighton Buzzard again. Yet another bust of a morning. Out of the blue, Claire emerged from the coffee shop, Americano in hand (I assume it was an Americano anyway). We had a few minutes until her train arrived, so I asked how things were. Same old, same old apparently. But she had started cycling to the station. She noticed the bike map in her handbag a couple days after I spoke to her, and it reminded her of our chat. She took some adult cycle training lessons, and bought herself a new bike. And she was now riding to the station most days. What's more, she had talked to some of her friends, and they had started riding at the weekends. All from a chat and bike map, and sheer blind luck you may assume. But you would assume wrong. Engaging with people is not a numbers game. Nor is it about trying to convince people. It is about showing people that you give a damn about them, their lives, and what is important to them. It is about listening - the most important part of engagement. And I mean really listening to people. The next time that you are thinking about public engagement, try this. Instead of listing out what you want to achieve from your next community engagement activities, list what you want others to achieve from it. Should they engage with you to be informed? To have an impact on what you are doing? Or to get their worries off their chest? And then how would you plan your engagement differently?

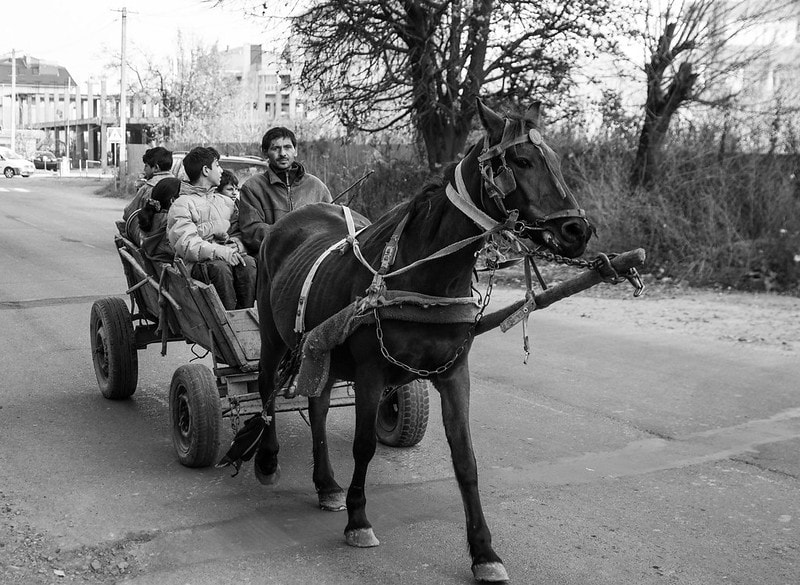

Simple questions like this change public engagement for the better. They are questions that we almost never ask in favour of our own objectives. Time to start asking them. If you haven't read Part One and Part Two of the story behind Mobility Lab, then I recommend that you do so before proceeding on. Also, just to note that the names in this post have been anonymised, and the pictures are random ones I found off the internet. Sadly, digital cameras were not widespread when I did these engagement events! "Why should I give you my view? You don't care. You just want to tick a box." "Ok, here's my view. The Council are useless and you should all be sacked. I've reported the p****s 5 times and nothing has been done about them." "Look, we just don't want the gyppos around here. Just blow up their caravans and be done with it." How do you overcome that level of vitriol in a public engagement exercise? Can you? When there is an out-group that is so hated, any form of public dialogue exposes some of the very worst in people. Not long after the disaster of my local transport plan consultation, I had the opportunity to observe a consultation exercise being run by Mid Bedfordshire District Council. This was the first of two such exercises on planning for Gypsy and Traveller sites across the district. The Council was required to identify suitable locations for new sites and pitches that could cater for their needs. This consultation was intended to share the first ideas. I was along for the ride as the transport expert. For those who are not aware of the status of Gypsies and Travellers in the UK, the attitudes to them amongst the majority of the public have been described as the last acceptable form of racism. The level of the debate that took place was exactly what I expected. Everyone was invited to have their say. Add in a spot of hatred, and what resulted was something worse. Lots of comments that were vile and contributed nothing. The planning officers were understandably anxious about planning the next round of events. They approached it with a management ethos. Lets just manage the comments. People won't like what we have to say, so lets take the hit and get it over with. I wasn't having any of it. 'Just managing' wouldn't happen. I started this turn around of the events by stating a simple observation: in all of the engagement exercises that we did, not one gyspy or traveller attended. Not. One. "We are creating a policy to benefit them, and they are not having a say in it. For what other policy would that be acceptable?" I asked during a meeting to plan the next round. "Why are we not talking to them?" We were guilty of much of the same prejudice that we had sworn as public policy makers to never let influence our decision making. We simply didn't know how to engage with people we were creating policies for. Worse than that, other policies actively worked against us. For example, ff we wanted to go onto a traveller site, our risk assessments stated that the only safe course of action (and thus the only thing covered by our insurance) was to have a Police escort onto the site. This made my plan seem mad. Simply talking to them was mad. That's mad. The plan that we eventually came up with was simple. We would first bring on someone who knew about all this better than the rest of us. So Simon came on board (I won't share his surname, as I know that he has had threats against him from supposedly 'decent' people). He advises planners and local authorities across the UK on gypsy and traveller issues. He knew how to get into the communities, and he knew them far better than we did. He first spent a day with us, downloading everything he knew. That the crime rate of those groups is no different to the national average, but they are more likely to be victims of crime and to be arrested than other ethnic groups. About their family structures, cultural norms and traditions. We learned so much in just 8 hours. His next job was to then set up meetings between ourselves and members of the gypsy and traveller community. To allow us to ask questions of what their needs are, and what they would like from the policy. We argued the hell out of this with our risk assessment teams. We eventually got a compromise. There would be at least 3 members of the team present, and no all-women groups on our side. Simon should also be present if possible. I personally attended two such meetings. Not only were the families warm and welcoming, but in 30 minutes with them I learned more about their site needs than I could have imagined. They wanted some extra pitches for visitors. They wanted good access to the main roads, and connections to electricity and water. They wanted the Council to take swift action against people who they knew would be trouble makers, and not against everyone in their community. They also told us that having a mix of types of site (some for permanent residents, others for transient populations) was critical. Naturally, ensuring the sites were safe and defendable was a major thing for them too. The second action we then took was more bold. For each of the planned public meetings, we wanted them to run differently. No longer would someone from the planning department presenting, and then opening up to questions / hate from the audience. The planners would set out why we are doing this. Then Simon would set out the facts about gypsies and travellers. Finally, and most boldly, we invited a member of the local travelling community to present their side of the story. The final part took a lot of convincing on all sides. You are essentially asking for a member of a community who is widely hated to tell everyone why they need help. It is a huge target on their head. For us, putting this to Councillors was almost impossible. "Why should those scum get to have a say?" said a Councillor who shall not be named. We stuck at it, and through sheer bloody-mindedness on our side, eventually the objections relented. On the advice that the local police officers be in attendance at each event. Some weeks later, our first event took place at Maulden Village Hall. An evening meeting. We knew from the Parish Council that a local action group had been established, and was planning to turn up en masse at the event. We also knew from Simon that 5 people from the local travelling community would be there. Councillor Shadbolt, our chairperson for the evening, joked to me that he had his riot gear in the boot of his car. At least I think it was a joke. As the room began to fill up, and with 10 minutes to go before we kicked off the meeting, we got into a huddle. As council officers, we must be neutral and sympathetic. Councillor Shadbolt needed to have a firm hand on the wheel. Simon needed to be authoritative and clear. Sean, the member of the local travelling community who would be speaking, just needed to be himself. Our game plan was a simple one. Take the sting out of the evening first, and then build empathy from there with a reasonable debate. 100 people were crammed into a small village hall. There were signs saying "No more travellers" and "Evict gyppo scum." Everyone was glaring at the 5 men who volunteered to put their needs forward. "This will get ugly" I thought. I thought wrong. The people there gave Simon the hardest time. There were howls of derision as he shared the facts that he shared with us. Councillor Shadbolt kept a firm lid on things. But then Sean began to speak. He told everyone present about his family. About how his mother, from when he was young, instilled in him a strong work ethic and family-first attitude. About how much he cared for his 2 young daughters, and how frightened he was for their future. Throughout his own life he had been randomly assaulted in the street more times than he cared to remember. His brother had been stabbed by a random teenager who stated to the police that all he wanted to do was "murder a gyppo." Luckily he recovered. He faced accusing looks all the time, and whenever something bad had happened in the local area, he knew the police would come knocking. In all the times he had been assaulted, the police only took a statement once. He worked hard. He paid his taxes. He spent money in local shops, and when people in his community got out of line he took action. He hated the worst people in his community as much as everyone else. And when he was asked why this policy was important, he answer was simple. "It gives me a home to defend, and to call my own. I don't have that." The room was stunned into silence. At the end of the evening, I mixed in with the people who were there. They all remarked on Seans speech, and how it challenged how they saw the travelling community. For most of them, it was the first time they had actually heard from a member of the travelling community. "I can't imagine what it must be like to live with the thought that at any moment you could be assaulted" said one. "Look, I still don't like the plans, but credit to that Sean bloke. Perhaps it is time we turned down the rhetoric a bit" said another. Simon was talking to Sean throughout. I learned later that Sean and his 4 friends felt really grateful for having the chance to have their say. And that they felt like someone was listening to them for once. We had achieved something quite extraordinary. By focussing our efforts on the people who really mattered, putting them and their needs at the centre, and challenging the mob mentality, we had made the engagement exercise more meaningful to everyone. This wasn't just through more positive public meetings. We spoke to 30 travelling families over 12 weeks, and made changes to our policies, including design and service standards for new traveller sites. We had letters from grateful members of the public thanking us for some excellent community meetings, and Councillors congratulated us on a great job. The majority of the comments we received were still objections. But hey, baby steps and all. This was how engagement should be. Put the people you are trying to help front and centre. You should empower them, not ask them for their view. You should really focus on who you want to talk to, and do everything in your power to make it about them.

This often involves knocking down barriers, blowing up rules, and challenging cultural norms. I can safely say that what we cut our teeth on was probably the hardest group imaginable because of the barriers that misconceptions of that group have created. We fought long, hard, frustrating battles on their behalf. Unseen. Good public engagement is not pretty, and too often public engagement gets tied up in methodology. Most of it is shitty work where you have to fight long, lonely battles for what is right, because you have the power to do so. Throughout a long summer, we fought those battles, and we won them. And our engagement was all the better for it. We won't lie about this. Completely changing how you engage with citizens as part of your transport work is hard. It is a long, challenging, and often frustrating process to go through. But the fact that you want to do it makes it worth it. And that desire will carry you through the times when this change is bad. Over the last few weeks, we have given some hints on how you can tweak your existing engagement processes to get more value out of them. Measurement, citizens assemblies, hacking traditional consultation, and public meetings. All good stuff. But all playing at the edges. You need to start something more radical. If you are in a situation where your local authority has identified that it needs to do community engagement better - congratulations, you truly are in a priveleged position! Your job will be so much easier. But for most of us, that is not the case. So what do you do to change things up when you are the lone voice calling for it? Be realistic and idealistic The first thing is to get in the right mindset, and set your expectations as to what you can achieve. You will need to play the long game to change people's hearts and minds, and demonstrate the value of what you do. From our experience, just the process of starting on a major bit of public participation to prove your idea will take at least 9 months. You have to win people over just to get a trial going, and that takes time before you consider doing the business case. To get one other senior manager fully signed up will probably take 12-18 months. Everyone? At least 2 years. Your idealism will drive your passion, which will be essential to getting this done. But people do not change their minds quickly, and need convincing all the time until they are signed up. Keep people updated on your success and issues. Show your enthusiasm, and spend time explaining the idea to them. And do it again. And again. And again. Until you are sick of doing so. Few people have their mind changed by a sudden Eureka moment. Advertisers know that a constant drip feeding of the message is more successful over time compared to a big bang and then nothing. Take that mindset to your work. A few passionate allies is better than a lot of interested people This was a big learning that we had from organising the Transport Planning Camp. A lot of people will say they are really interested in the idea and want to be involved. But only a few will come through be a meaningful ally who you can rely on. Seek them out, and hold onto them. In an ideal world, these allies will be in senior management positions. But a good ally is a good one regardless of their position. Not only will you all work together to actually put what you need to do into practice, but they are an invaluable support network for you. Sharing war stories and laughing in the face of adversity helps far more than you think it does. What helps cement this is having a defined goal to work to - an event is usually a good way of doing this. Or it can be as simple as having a common aim, and a commitment to getting together for coffee once a month. Understand your own power It is easy to feel powerless, especially when the manager says no. But you have far more power than you give yourself credit for. You just need to understand how to use it. Understanding the power dynamics, as well as where formal power actually lies, is probably the best thing you can get your head around. Who influences who? Who is the dominant voice at board meetings? Who do the decision makers trust most? What are your personal relationships with the decision makers like? Are they easily persuaded. It is a good idea to visualise this if you can. Draw a spider diagram on a peice of paper with all of the key decision makers that you can think of, with you in the middle. Visualise the relationships between the different decision makers - say a different colour pen representing the strength of their relationship. Write where the formal decision making power lies, and for what. Just this exercise will give you an overview from which you can plan. You will see people to avoid, who would be sympathetic to your view, and who you can target for the biggest impact. And then what you can do to exercise your own power in a way that has the biggest impact. The best case for change is change itself This is so cliche. But it is true. If you want to show the case for change, then you have to show it. That means securing time and resources for a small trial of your approach. Trials are great. For a limited amount of effort and resource you can prove an idea (or disprove it - its a trial after all). But when you make the case it has a huge advantage over a worked up project - you sell it based on the problem, not on the solution. The way our brains work is that we almost always focus on the problems and challenges first, before the solutions and the positives. That's what comes from thousands of years constantly monitoring for threats from animals that can eat us. By focussing the case for your trial on how bad the challenge is, 80% of your battle is won. The remaining 20% is you stating how your trial could - if given the chance - help to overcome this. For example, if you are having problems reaching a particular transport user group, you may wish to pilot a user survey delivered in partnership with a local community group who works with that group all the time. By stating how hard it is to reach that group, and how this limited trial could get some really useful insights on that group and prove whether or not the concept works, that is a compelling case. Finally, plan for afterwards

You have done a pilot. It has gone well and you have all the evidence that you need to make community engagement the heart of your transport work. But this is where a lot of projects fail. They do not plan for afterwards, and ensuring a lasting impact. Think about the practicals first. Chances are you won't have any more dedicated funding, or much time, to continue the work immediately afterwards. So think about how you will continue to convince people of the merit of this work afterwards. And do this before you start, so that you can build it into the work of your project (e.g. inviting key decision makers to a workshop). How will you continue to convince people post-trial? Will it be possible? And if not, should you go for another trial instead? Also, plan for failure. Your trial may fail completely, and may undermine your case for further work. Think about what this will mean for how you plan your changes in the future, and at what point it may be best to call it a day. Change is hard. Extremely hard. But anything worth doing has always been hard to do. And the best thing is that people have done it before. Here are our key lessons for what makes for successful change. In every profession you get these old adages - accepted wisdoms about how the world works, and the attitudes that are impossible to shift. Transport planning and community engagement have a few of them. But there is one that they have in common that, more than most other things, drive how things are done. You are what you measure. The key performance metric - whether it be number of bicycles along a road or the percentage of people travelling sustainably - drives almost everything. It is the purest interpretation of what you are trying to achieve. Something to which all actions should contribute towards. Community engagement is no different to this. When you are planning how you engage with citizens, you have to be able to demonstrate the impact of your engagement. Warm, fuzzy feelings about how well it went, and informal feedback saying you did a good job does not do that in a defendable way, sadly. Nor does telling anyone quite how many people came through the doors at your public exhibition. You need KPIs to show what did made a difference. You need KPIs over time to show that you have tried different things to engage with people, and this is the impact of what you have done. So how on Earth do you choose the right one? Think about what you want to achieve from your engagement over time This is such an obvious bit of advice. But we are always amazed at how people spend ages thinking about their objectives for their community engagement activity, before just counting the number of people who attended. Come up with one KPI for each of your engagement objectives, and weave how you will monitor that into your plans for the engagement activity. Do not leave it as an afterthought, because if you do then the data you collect will be next to worthless. Few people voluntarily complete a survey form. Even better, think about how you can standardise that data collection across your activities. So that you are not having to reinvent the wheel all the time. Collect attitudes, not just opinions or demographics It is really easy to ensure that you have a cross section of people attending based on simple demographic information, and how your activity compares to others. It is also really easy to ask people for their opinions - hey, you are doing it through this exercise aren't you? But had you thought about attitudes? How are you making sure that who is taking part in your engagement activities reflects a diversity of worldviews? How can you be sure that as well as the ardent cyclists, you also had the Jeremy Clarkson's of the world represented. Needless to say that this is an extremely tricky thing to do, especially when you don't have a baseline already. Except you may have. Your public engagement team are likely to be running an attitude survey of citizens all the time, asking for their general attitudes on everything from the state of the world, to how positive they feel about the world. Hey, we even have the British Social Attitudes Survey. Pick a metric, and think about the ways you can ensure that different people with different attitudes are represented. Measure engagement, not activity The number of people who I have seen set up a wonderful consultation website, and then just monitor the number of visits is infuriating. A shop always counts the number of sales that it makes, not the number of people looking in the window, and you must take the same approach to measuring the impact of your engagement. Online this is easy. Using systems like Google Tags means that not only do you count the visits, but you can look for specific activities that you want people to do. For example, rather than counting the website visits, why not count the number of times people posted comments, or sent theirs in through an online form? That way, you are measuring what matters. Offline and in the real world this is more tricky. You can count the number of feedback forms, the number of ideas generated per attendee at a workshop, and the tone of that engagement. All are difficult to do well, and are ripe for your experimentation. It is something that we are still experimenting with ourselves. Defining what is a good KPI is an art in itself. And in many respects there are no right or wrong KPIs. Even measuring the number of people who have turned up is not a bad metric per se. But too often we focus on counting things, and surveying what is most tangible. Because it is easy. Your KPIs for your engagement activity should stem from what you want to achieve, not from what is possible. Otherwise, how will you know if you are achieving it?

We know what it is like. Even if you put in all the effort to run engaging workshops, creative online surveys, and you may have even deployed virtual reality and your public exhibitions. But at some point, you still have to run consultation the traditional way – a 12 week consultation, where people can write in or email their views to you. And local authorities still receive a lot of comments that way. Recently, I spoke to a strategic transport body that received over 100 responses to a policy document as part of a consultation. Responding to each one individually is a time-consuming and intensive task. Luckily there are ways by which you can hack this. Where you can properly consider the comments, respond well, and cut down on the time that you spend responding to them. Set up a response process Planning is everything. The worst thing that can happen is for messages to pile up in the inbox and in tray, to be dealt with once the consultation closes. So take the time to set up a basic process before your consultation goes out, which manages each message as it goes through. Then set up a rota with all involved in the consultation process, and stick to it. When I have managed inboxes for consultations, I have split them into 4 folders. These are:

Then, i know that any email that is in the inbox itself has not been dealt with, and is in most need of attention. Where there has been more than one person working on the responses, keep the same folder structure as above, but as sub-folders under a folder for each person. Take the time to acknowledge receipt This seems counter-intuitive. How is taking more time to acknowledge receipt of someone’s comments saving time? Simple. An information black hole is one of the worst things for consultation. By saying thank you, and importantly giving a timescale by which you hope to respond to them in detail, you are saving yourself by stopping them from chasing you later when you tell them nothing. Also, people will actually like the fact you have acknowledged them. Whatever you do, DO NOT set up an automated email with a standard response. That is lazy, and gives the impression you are fobbing them off. Nor do you need to type a different acknowledgement each time. A good hack is to have a selection of 10 pre-prepared acknowledgement responses in a document, and when an email comes in, copy and paste one of them and send it. Hack your reading We’re sorry to say this, but you cannot get away from reading the responses. But there are ways that you can make it easier, and boost your reading speed at the same time. Firstly, reflect on when during the day your concentration is the best. For most people, this is usually the morning, often during late morning after the body has warmed up and the brain has got into its rhythm. It is often best to avoid reading responses in the afternoon, as your brain begins to tire. Also, do other reading apart from just the consultation responses. The best way to improve your reading speed is to…read! Read magazine articles, newspapers, books, something that you enjoy reading. And it will boost the speed at which you read other things. You should also not read the responses in your head. This is really hard to do, as we are taught to read by speaking the words, and we carry on this trait by speaking the words in our heads. This substantially slows down your reading time to the pace at which you speak. So practice not reading in your head, or distracting the internal voice by playing music. Finally, whatever you do, do not read a passage several times. This means that by the time you read a response once, you have in fact read it several times because you have been constantly going back over words. Do not do this. If you must, come back and read the whole thing again later. Categorise the issues raised, and form basic responses for each of them

By the time that you have read many responses, chances are you will notice very similar messages coming through. People want buses improved, they have an issue with a particular junction, or even they have literally copied and pasted a letter sent by someone else. Use this to your advantage. Craft a basic response to each of these issues raised. Almost a common structure to how you will respond to that issue. But do not copy and paste that specific response to each person. Use it as a basis to provide a more personal response. For example, instead of responding with… “Improving walking and cycling infrastructure across the city is a priority as identified in the Local Transport Plan.” …use that response as a basis to say… “Improving walking and cycling infrastructure in your neighbourhood is a priority as identified in your neighbourhood delivery plan.” Subtle changes, without having to type out the same sentence again and again. Often, it is such small changes that are seemingly insignificant that can save you a lot of time as you respond to consultations. Without giving your citizens the bland, general responses that make them feel like they don’t care. Give them a try, see what you think. |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed