|

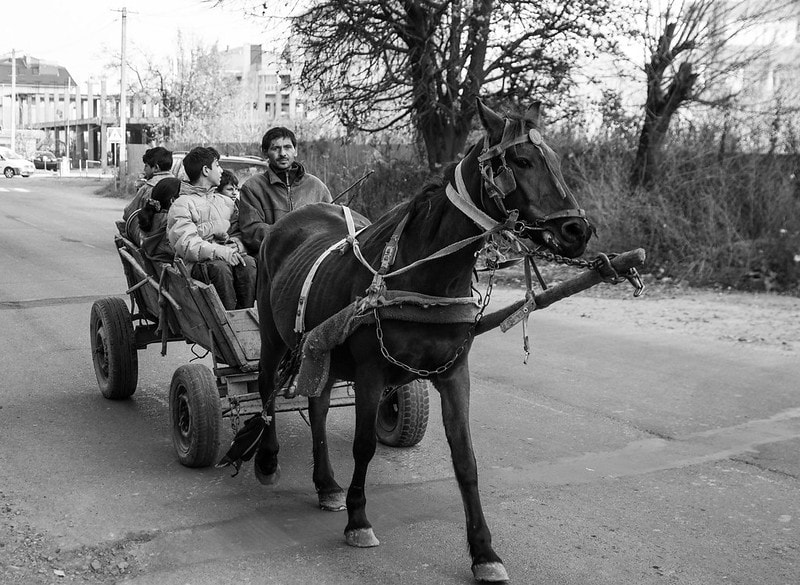

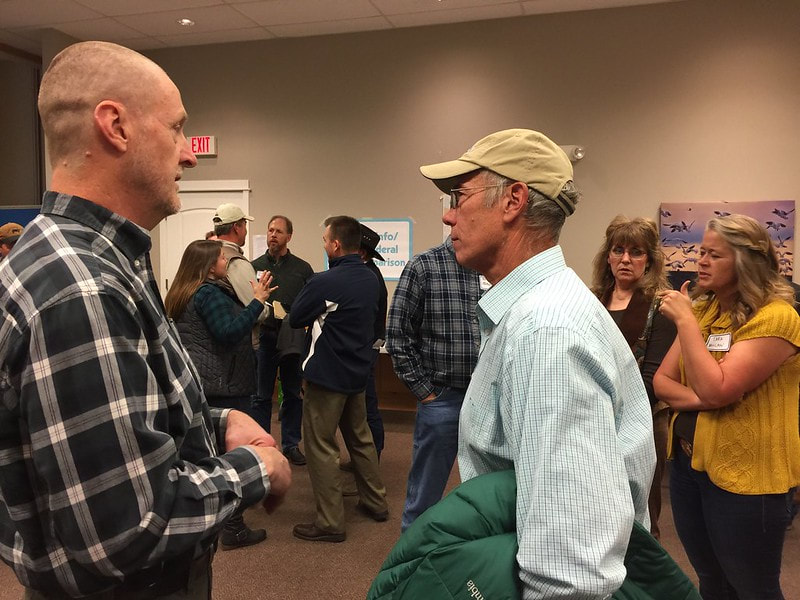

If you haven't read Part One and Part Two of the story behind Mobility Lab, then I recommend that you do so before proceeding on. Also, just to note that the names in this post have been anonymised, and the pictures are random ones I found off the internet. Sadly, digital cameras were not widespread when I did these engagement events! "Why should I give you my view? You don't care. You just want to tick a box." "Ok, here's my view. The Council are useless and you should all be sacked. I've reported the p****s 5 times and nothing has been done about them." "Look, we just don't want the gyppos around here. Just blow up their caravans and be done with it." How do you overcome that level of vitriol in a public engagement exercise? Can you? When there is an out-group that is so hated, any form of public dialogue exposes some of the very worst in people. Not long after the disaster of my local transport plan consultation, I had the opportunity to observe a consultation exercise being run by Mid Bedfordshire District Council. This was the first of two such exercises on planning for Gypsy and Traveller sites across the district. The Council was required to identify suitable locations for new sites and pitches that could cater for their needs. This consultation was intended to share the first ideas. I was along for the ride as the transport expert. For those who are not aware of the status of Gypsies and Travellers in the UK, the attitudes to them amongst the majority of the public have been described as the last acceptable form of racism. The level of the debate that took place was exactly what I expected. Everyone was invited to have their say. Add in a spot of hatred, and what resulted was something worse. Lots of comments that were vile and contributed nothing. The planning officers were understandably anxious about planning the next round of events. They approached it with a management ethos. Lets just manage the comments. People won't like what we have to say, so lets take the hit and get it over with. I wasn't having any of it. 'Just managing' wouldn't happen. I started this turn around of the events by stating a simple observation: in all of the engagement exercises that we did, not one gyspy or traveller attended. Not. One. "We are creating a policy to benefit them, and they are not having a say in it. For what other policy would that be acceptable?" I asked during a meeting to plan the next round. "Why are we not talking to them?" We were guilty of much of the same prejudice that we had sworn as public policy makers to never let influence our decision making. We simply didn't know how to engage with people we were creating policies for. Worse than that, other policies actively worked against us. For example, ff we wanted to go onto a traveller site, our risk assessments stated that the only safe course of action (and thus the only thing covered by our insurance) was to have a Police escort onto the site. This made my plan seem mad. Simply talking to them was mad. That's mad. The plan that we eventually came up with was simple. We would first bring on someone who knew about all this better than the rest of us. So Simon came on board (I won't share his surname, as I know that he has had threats against him from supposedly 'decent' people). He advises planners and local authorities across the UK on gypsy and traveller issues. He knew how to get into the communities, and he knew them far better than we did. He first spent a day with us, downloading everything he knew. That the crime rate of those groups is no different to the national average, but they are more likely to be victims of crime and to be arrested than other ethnic groups. About their family structures, cultural norms and traditions. We learned so much in just 8 hours. His next job was to then set up meetings between ourselves and members of the gypsy and traveller community. To allow us to ask questions of what their needs are, and what they would like from the policy. We argued the hell out of this with our risk assessment teams. We eventually got a compromise. There would be at least 3 members of the team present, and no all-women groups on our side. Simon should also be present if possible. I personally attended two such meetings. Not only were the families warm and welcoming, but in 30 minutes with them I learned more about their site needs than I could have imagined. They wanted some extra pitches for visitors. They wanted good access to the main roads, and connections to electricity and water. They wanted the Council to take swift action against people who they knew would be trouble makers, and not against everyone in their community. They also told us that having a mix of types of site (some for permanent residents, others for transient populations) was critical. Naturally, ensuring the sites were safe and defendable was a major thing for them too. The second action we then took was more bold. For each of the planned public meetings, we wanted them to run differently. No longer would someone from the planning department presenting, and then opening up to questions / hate from the audience. The planners would set out why we are doing this. Then Simon would set out the facts about gypsies and travellers. Finally, and most boldly, we invited a member of the local travelling community to present their side of the story. The final part took a lot of convincing on all sides. You are essentially asking for a member of a community who is widely hated to tell everyone why they need help. It is a huge target on their head. For us, putting this to Councillors was almost impossible. "Why should those scum get to have a say?" said a Councillor who shall not be named. We stuck at it, and through sheer bloody-mindedness on our side, eventually the objections relented. On the advice that the local police officers be in attendance at each event. Some weeks later, our first event took place at Maulden Village Hall. An evening meeting. We knew from the Parish Council that a local action group had been established, and was planning to turn up en masse at the event. We also knew from Simon that 5 people from the local travelling community would be there. Councillor Shadbolt, our chairperson for the evening, joked to me that he had his riot gear in the boot of his car. At least I think it was a joke. As the room began to fill up, and with 10 minutes to go before we kicked off the meeting, we got into a huddle. As council officers, we must be neutral and sympathetic. Councillor Shadbolt needed to have a firm hand on the wheel. Simon needed to be authoritative and clear. Sean, the member of the local travelling community who would be speaking, just needed to be himself. Our game plan was a simple one. Take the sting out of the evening first, and then build empathy from there with a reasonable debate. 100 people were crammed into a small village hall. There were signs saying "No more travellers" and "Evict gyppo scum." Everyone was glaring at the 5 men who volunteered to put their needs forward. "This will get ugly" I thought. I thought wrong. The people there gave Simon the hardest time. There were howls of derision as he shared the facts that he shared with us. Councillor Shadbolt kept a firm lid on things. But then Sean began to speak. He told everyone present about his family. About how his mother, from when he was young, instilled in him a strong work ethic and family-first attitude. About how much he cared for his 2 young daughters, and how frightened he was for their future. Throughout his own life he had been randomly assaulted in the street more times than he cared to remember. His brother had been stabbed by a random teenager who stated to the police that all he wanted to do was "murder a gyppo." Luckily he recovered. He faced accusing looks all the time, and whenever something bad had happened in the local area, he knew the police would come knocking. In all the times he had been assaulted, the police only took a statement once. He worked hard. He paid his taxes. He spent money in local shops, and when people in his community got out of line he took action. He hated the worst people in his community as much as everyone else. And when he was asked why this policy was important, he answer was simple. "It gives me a home to defend, and to call my own. I don't have that." The room was stunned into silence. At the end of the evening, I mixed in with the people who were there. They all remarked on Seans speech, and how it challenged how they saw the travelling community. For most of them, it was the first time they had actually heard from a member of the travelling community. "I can't imagine what it must be like to live with the thought that at any moment you could be assaulted" said one. "Look, I still don't like the plans, but credit to that Sean bloke. Perhaps it is time we turned down the rhetoric a bit" said another. Simon was talking to Sean throughout. I learned later that Sean and his 4 friends felt really grateful for having the chance to have their say. And that they felt like someone was listening to them for once. We had achieved something quite extraordinary. By focussing our efforts on the people who really mattered, putting them and their needs at the centre, and challenging the mob mentality, we had made the engagement exercise more meaningful to everyone. This wasn't just through more positive public meetings. We spoke to 30 travelling families over 12 weeks, and made changes to our policies, including design and service standards for new traveller sites. We had letters from grateful members of the public thanking us for some excellent community meetings, and Councillors congratulated us on a great job. The majority of the comments we received were still objections. But hey, baby steps and all. This was how engagement should be. Put the people you are trying to help front and centre. You should empower them, not ask them for their view. You should really focus on who you want to talk to, and do everything in your power to make it about them.

This often involves knocking down barriers, blowing up rules, and challenging cultural norms. I can safely say that what we cut our teeth on was probably the hardest group imaginable because of the barriers that misconceptions of that group have created. We fought long, hard, frustrating battles on their behalf. Unseen. Good public engagement is not pretty, and too often public engagement gets tied up in methodology. Most of it is shitty work where you have to fight long, lonely battles for what is right, because you have the power to do so. Throughout a long summer, we fought those battles, and we won them. And our engagement was all the better for it.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed