|

For the last few months, we decided to be quiet. Our usual weekly email has not gone out, and our social media content has redueed to virtually nil. We did this without notice, and you deserve to know why. Like everyone else, we have been side-swiped by this pandemic. Not financially so. In fact, we have picked up three amazing projects in Southend, the Solent, and Nottingham, and we have been working with amazing strategy teams and communities in all 3 of these areas. And being busy has also been part of it. Our New Normal project goes from strength to strength. Our TPS COVID-19 project is being finished off. Transport Planning Camp Extra was a blast. And we are in the process of creating 3 new services, to be introduced over the next year. But this doesn't explain our silence. What does is a simple fact that we came to realise during the pandemic. Working quietly and in the background is our strength. We first realised this as we worked on the New Normal project. When researching new visions of the future of transport after COVID-19, we were shocked at the sheer lack of variety. Those that are shared are the same visions as they have always been. As though nothing has changed in the world. We kept thinking "a pandemic has swept the world, and your vision is the same one you have had for 10, 15, 20+ years? Has nothing changed?" We also kept asking what voices were missing. With protests sweeping the world, surely the voices of traditionally excluded groups need amplifying, and their visions need sharing? Where are the visions of of ethnic minorities, feminists, the LGBTQ community? Sod it, even the visions of people who don't have degrees (which 95% of our followers have)? We also learned from our many failed experiments during this pandemic. Our daily updates on YouTube that we found out after a few days that we hated doing. In our online workshops where we tried new techniques for group discussions that bombed spectacularly. Live Streaming our Scenario Planning training where not only did our live stream give out, but it also felt really uncomfortable streaming through YouTube. We also tried to create two groups which tried to pressure for change, including walking and cycling improvements in our home town. We came to realise that the way we are doing things not only didn't really empower people, but it didn't really make us happy either. We find happiness in being in the background, and empowering others in softer and more subtle ways. To use a transport example, whenever we plan for transport we plan for the needs of passenger transport. Because that is what we experience directly. In some ways, it is the 'sexy' part of transport planning that everyone talks about and has an opinion on.

What we came to realise is that we are more like freight. We are there, in the background, just making sure that what we do works well and gets done. And that thing is empowering others to do things. In the same way that freight gets food to the shelves in shops and delivers the materials needed for literally everything in your home apart from the people. We are best when we are organising, and we are doing things that knock down barriers and empower people who want to make the change by making that change easier. The first step in doing that, is shutting the hell up. There are far too many people in the world who talk a lot, and whose role it is to lead the charge. We are not those people, and for too long we tried to emulate them for no good reason. We will still state our view on things occasionally, and share with you some of the work that we have been up to. But we will keep what we say to times and issues where we feel we will have a meaningful impact. We have been practicing this over the last few months, and we are the happier for it. We are now working on projects and with clients where we are genuinely empowering others to do transport and citizen engagement better. We are loving it. It just took us a pandemic to realise this.

1 Comment

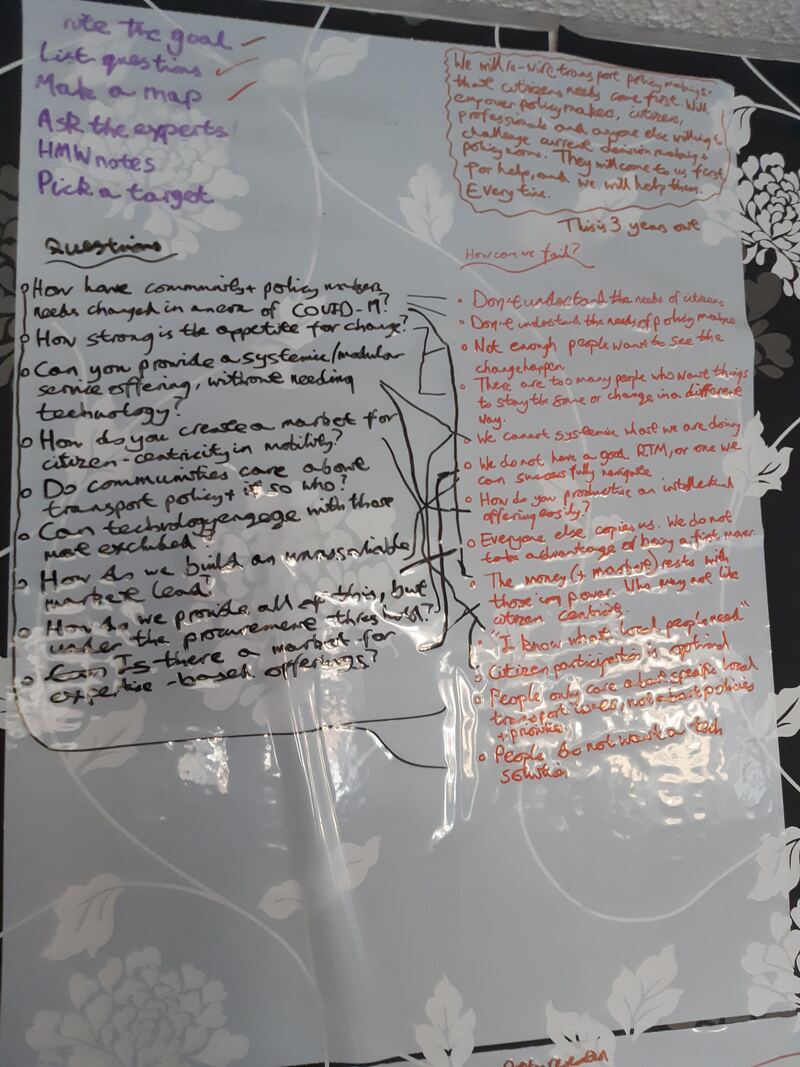

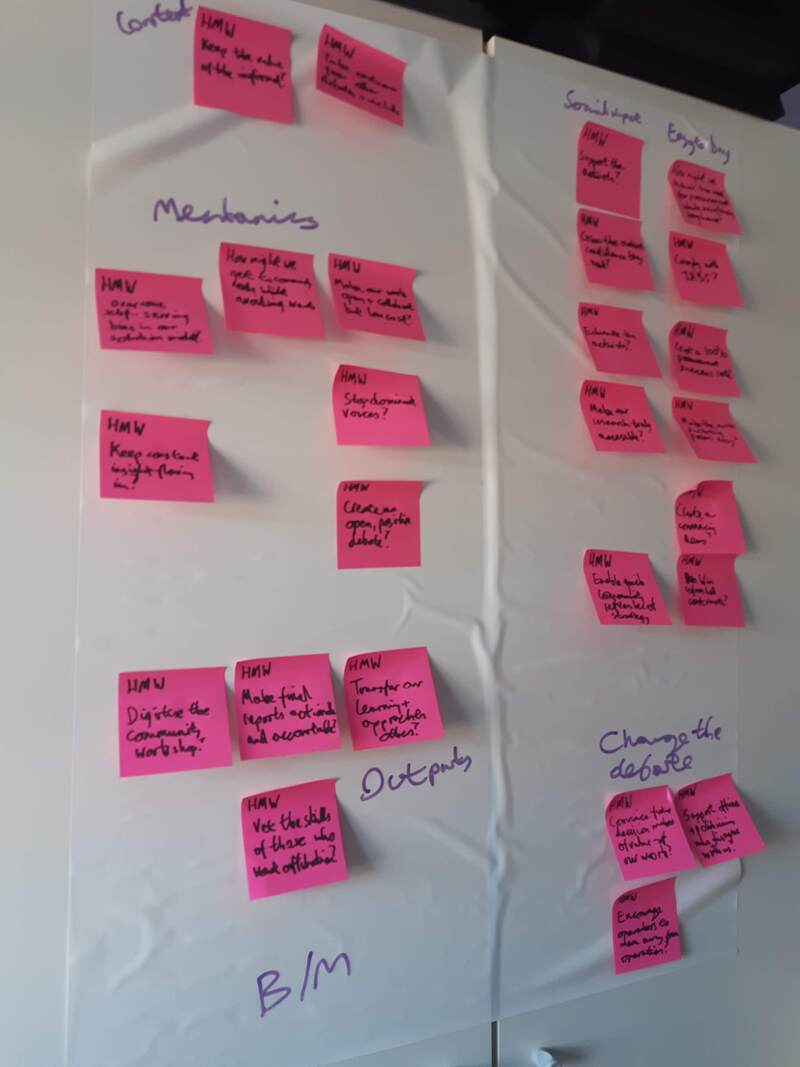

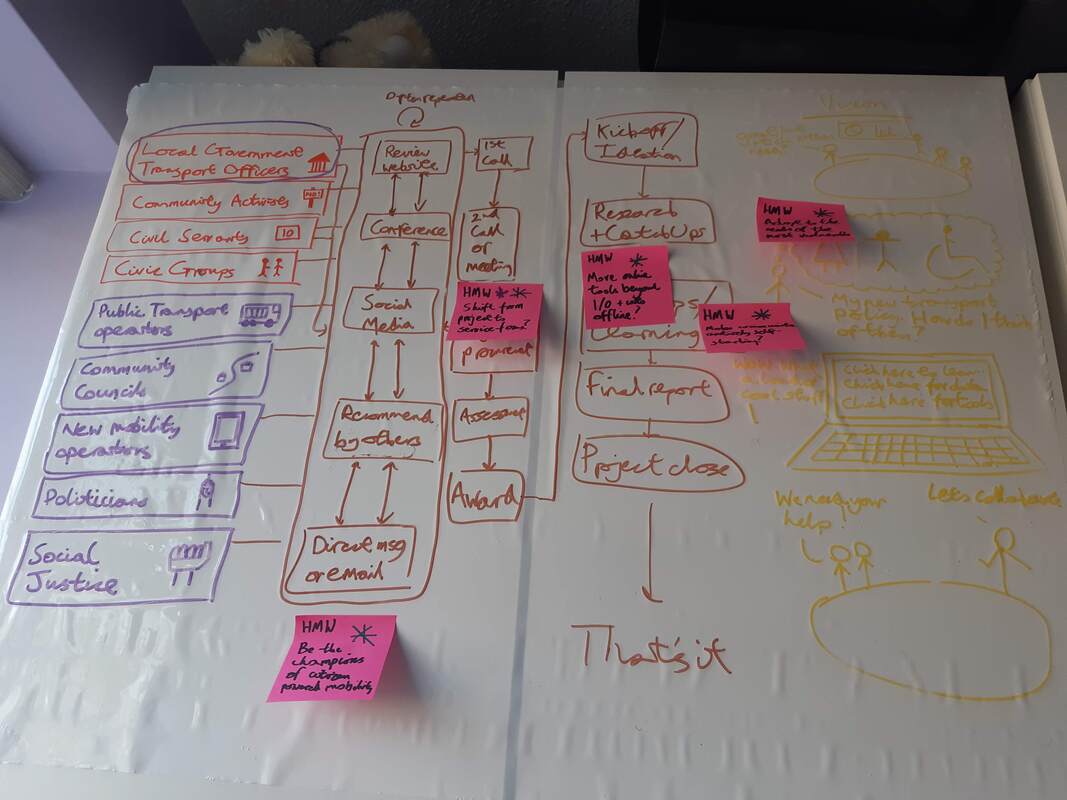

If you want to skip the background, and straight to the end, we want to talk to transport planners and activists this coming Wednesday about a service we are developing. Links to book a time are at the end of this post. Before we start - how are you? I hope that you are keeping safe and well during this turbulent time. I hope that your family, friends, and communities are keeping well, and that you feel supported. For us, we feel like we are in the eye of a hurricane. The chaos is raging, and it is within touching distance. But there is a strange calmness that belies the danger all around. But we are using this calm to do and think anew. You may have already seen our international research project New Normal? and the work we are doing to support the Transport Planning Society. In this post, I am calling for your help in reshaping what Mobility Lab will look like. We need it, quickly. I mentioned in a previous post how we were planning to accelerate our tech development. We kick started this process last week, and very early on came to realise that our original plans were great...for when we originally came up with them. Our entire context had shifted, and so our plans needed a big shift as well. So I started off a business design sprint. Reviewing our current processes, and our original plans, and mapping out how they work, and whether they still apply in this new world. Here's a clue: they didn't. Well, kind of didn't. Whilst the processes that many of our potential customers go through is still the same, the feedback that we got was that process on community engagement and transport was being overtaken by events. I chose a sprint as the most appropriate method for two reasons, both related to the fact that time is of the essence. Firstly, we want to shift away from our current consultancy focus as this is not applicable in a time when the need for doing good things is great, and finances are stretched. Secondly, there are opportunities for government support to help us create something of immense social value, whilst shifting our operational model, but they close very soon. So what are we looking to build? Well, I am still in the process of the sprint right now. But the key conclusions that we have identified so far are as follows:

This, in a sense, is the problem statement. Previously. an online engagement platform was a very much a digital tool for an analogue age. Whatever the solution is, it needs to be a digitally-analogue tool for a digitally-analogue age. When I mapped our current service offering, and how we might make significant improvements, it was clear that a shift in the operational model is essential if we are to answer many of the questions posed in this new reality. Now, I need your help.

If you are a city or local authority transport planner, or you are an activist, I need to talk to you. All I need is 30 minutes of your time to run the solution idea past you. It is essentially a sense check on what we are proposing, and how we could make it better. What do you get from it? Is a good feeling not enough :)? In all seriousness, when we develop the final solution, we will give you a discount. On this coming Wednesday (15th April 2020) we are offering the below 30 minute slots for a chat. All you have to do is book them. 12 - 12:30pm - Book now 12:30pm - 1pm - Book now 1pm - 1:30pm - Book now 1:30pm - 2pm - Book now 2pm - 2:30pm - Book now 2:30pm - 3pm - Book now 3pm - 3:30pm - Book now 3:30pm - 4pm - Book now If you have any questions, you can just email us. Otherwise, we look forward to chatting to you. We won't waste your time. No doubt your head is spinning with what has happened over the last week. So here is what we plan to do to help you through this all.

My, how a crisis focusses the mind. Our scenario planning training is going online From our discussions with good friends over the last week, what has been clear is that many need the tools to make good decisions, and now. So we are taking our popular Scenario Planning for Transport training online. We are currently restructuring the course so that participants can collaborate much more easily. Not only are we looking at tools which will allow remote collaboration, but we will also be more flexible on how it is delivered. For example, as opposed to having to dedicate two whole days to training, we will experiment with 4 half days over a couple of months. You can get an idea of the topics we will be covering on the course page. The course will be delivered by Zoom, Skype, Hangouts, or whichever conference calling system you have. We are able to offer the course to all time zones, so even if you are on the other side of world, we can help. We will be offering online courses from 1st April, but we are open for bookings now. If you are interested, then email us. Rapid-fire trend analysis for a changing world We regularly get asked what are the biggest trends in mobility and the civic space, giving our insights into what is happening. COVID-19 changed all that. Not only do people want this insight, they want it now, as they need to make a decision now. People's livelihoods are on the line here. All the while, traditional transport planning and strategy making in cities continues onward, but with already stretched officers having to muck in with keeping public services running. Or deal with the kids at home. So we are going to formalise this. We have done some work to set up a simple process where you can go from an initial inquiry to us producing a tailored trend report for you within a week. This is mainly aimed at city authorities who want to create citizen-centred mobility policies but are now struggling for resource to deliver it. But if citizen-centred mobility is your thing and you are a company or community group, it works just as well. You can find out more about how it works on our dedicated web page. We are charging for this, but if you are an NGO or community group there is a discount. We are not fussed how we present our findings to you - whether slide deck or through video conference. All that matters is that will help you keep the long view in mind. Things like climate change an inequality will still be here once this is all over. We are supplementing this by working hard on a free-to-use trend deck, based upon our horizon scanning work. This will be available in early April. If you want to get started, email us. Bringing out the post-Corona view We know that there are a million conversations taking place across mobility about what a post-Corona (PC?) world will look like. We are assisting in many of those conversations, and having our own of course. But these conversations need joining together to develop a collective view of different futures. We have started some conversations with many good people in Europe, the USA, and New Zealand about creating a huge online conversation on 'Mobility PC' (working title that we just came up with). We will be using open tools and innumerable conversations to collect the data and signals of change, and to collectively analyse to develop these future scenarios. Oh, and we will be doing it for free, and in the open. This will be a lightning quick task - from start to completion within 6 weeks, with a crazy amount of work in between where the only reward is the kudos. We need volunteers to help make it happen. People to host online chats, to provide their evidence, to crunch numbers, and to help analyse potentially reams of feedback. It's a big ask for exceptional times. But if you are up for it, then get in contact with us. We are accelerating our tech that will get communities engaged in strategy making We must admit that we have fallen behind on our initial plans to get a beta developed for our online engagement platform. But despite us having to keep 2 metres from one another, the demand for community engagement will not go away. We are already talking to local authorities about how we can engage communities in their scenario planning work. Delphi studies and facilitating online discussions is something that we can do for you (at a charge), but its not quite what we are after. So by early April, we will publish our plan. And within 6 weeks will will have an alpha of our solution published. In the meantime, we are working closely with Annette, German, and the brilliant team at Future Fox on their online community engagement tool for streets and placemaking. If you want to talk community engagement right away, contact them. Our whole world has shifted overnight. We are all working like crazy to make sense of it all, to support ourselves, and to support the most vulnerable. Suddenly the world has become a crazier and more frightening place.

We are trying to do our bit in all of this. From the big changes outline here to the lending a helping hand to those who live near us who truly need our help. All whilst keeping the long view and the needs of people in mind. We wish you all the best. Remember, we are here for you if you need us. We can give you tools, pause for thought, and give you a new way of thinking about the world. Or just a virtual cup of tea. Stay safe, and stay positive. This is the final post on the history of Mobility Lab, If you haven't checked out Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, or Part 7, then you should before reading on. Have you ever had that moment in your life when you just knew what you were doing was the right thing? It may come when everything else in life is going to hell. Or you just feel completely broken. It may not even make any logical sense. Its just...that feeling. You may even get the chance to feel it more than once. For us, it came in Manchester in November 2019. On the day of the second Transport Planning Camp. On a day when Manchester really out-Manchestered itself on the weather front (a months worth of rain in one day), and a day full of energy and positivity. And Transport Planning Camp was a brilliant day. But we were not firing on all cylinders that day. The day came right in the heart of when it was the worst for us. We were tired, beaten down, and just wanted to crawl in a corner and hide. As we say, the day was brilliant and the energy was amazing. We just couldn't get into the mood. The day ended, everyone packed up, and went the pub for a social. But we stuck behind for another appointment. Her name was Kitti, a transport planner for whom we were acting as mentor for her Transport Planning Society Bursary. She had also attended Transport Planning Camp. "Just a catch up" it was meant to be. And it was. We talked about climate change and airports, her methodology, her research challenges, and went through some draft sections of her paper. It was good stuff. Really good stuff. Making research a compelling read is an art that Kitti is clearly good at. But as we packed up, she said something that was a throw away comment in any other conversation. "This is how things should be. Challenging others in a positive and open way. Today was fun!" On the train back south (one of the few running that day) we reflected on that comment. What we had done during the 18 months that we had been in existence came flooding back to us. Working with Piia, Si, Giles, Beate, and Laura to deliver a brilliant Open Mobility Conference in Brussels in 2018 as part of Travelspirit. Delivering not just one, but two excellent Transport Planning Camps. Which would not have been possible without the work of Anna, Pawel, Laura, Rachael and Kit. Working with Jenny, Tracy, Stephen, and Steve on a Discovery Project in the Scottish town of Inverurie. Finding out about the needs of rural residents in a really rural area (sorry Jenny - it may not be rural by Scotland's standards but it is rural!). Seeing people inspired to bring new ideas to the table was worth the effort of the project on its own. Having the chance to work with Milton Keynes Council on their evidence gathering for their position papers on walking and cycling, road safety, and smarter choices. Working with James, Steve, Hayley, Sara, Jackie, and Ishwer was amazing. Whilst we did not have the time to complete it, a big thank you to Victoria for getting it over the line! We had the pleasure of co-authoring not one, but two papers with Teresa and Nic. Not to mention taking part in two events with them at Transport Practitioners Meeting 2019 and Highways UK. And we authored a paper of our own. We ran our first two Scenario Planning for Transport Planners sessions, thanks to the help of Michelle and Brogan. And the feedback from participants has been amazing! And we got accepted onto the Natwest Entreprenuer Accelerator to boot. Not to mention the thousands of conversations on the current and future state of transport, openness, civic engagement, and everything in between. Reflecting on all of that as the train sped through the Staffordshire countryside with a whisky in hand (on the rocks) also made us reflect on the meaning of success and achieving your goals. We are firmly in the school of thought that if it feels right, then we have achieved success. But the funny thing about being in business is how the meaning of that success needs to be distilled into a metric of some sort. A sales target, a goal for growth, customer engagement rates, likelihood of success, percentage of the product complete. Modern business is full of them. Don't get us wrong. Some metrics are extremely important. Particularly the ones entitled 'income' and 'expenditure.' But the feeling of doing something right has to be written into that measure of success. We could be hitting our sales targets and income growth targets all the live long day, which would be for nothing if the feeling was empty. Coming around to this way of conducting yourself as a company takes time, and a lot of mistakes. It was a process that we needed to go through and learn the hard way. We do not believe in fate or anything like that, but perhaps on this occasion it gave a helping hand. Kitti was the spark that put the final peices of the puzzle together. The puzzle of why we are here as a company, and the sorts of things that we need to do in the time that we have on this Earth to make a difference. To leave our own little mark. Our reason for being is now caputured in our vision. And its a simple one. Such a change will be hard. It certainly won't mean we will become a major transport consultancy company. But that was never the point to begin with. The point is to change things for the better, and to start serving the people for a change.

We are now in a position where we are targeting projects where doing so is possible. We will share what we do, and the tools that we build. We will help everyone learn and build new skills. And we will kick arse whilst doing it. This is the penultimate post on the history of Mobility Lab, If you haven't checked out Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 or Part 6, then you should before reading on. Compared to a lot of other people in the world, we have lived a relatively priveleged life. Don't get us wrong, we have known suffering and hard times. Growing up in a working class neighbourhood in the UK in the 1980s meant there were some evenings where we did go without a meal. But it wasn't what we would call true suffering. Certainly not compared to the increasing number of homeless people that are now too common. But everyone experiences dark times. And so that characterised the early days of Mobility Lab. Before all of that, we spent 18 months back in local government at Buckinghamshire County Council. We spent that time leading the Sustainable Transport Team. A lovely team of 5, they delivered far more than their small budget belied. As well as managing all of the 70-plus School Crossing Patrollers, Corinne and Gina led a number of sustainable travel initiatives including Bikeability training, training the Junior Road Safety Officers. Fiona organised the largest programme of health walks of many-a local authority, and loved every second of it. Nicky, and then Kathryn, kept over 100 schools enthusiastic for sustainable travel. All brilliantly led by Katie. The wider Transport Strategy Team were pretty awesome as well. Not only writing strategies, but winning big amounts of funding for transport schemes, and keeping the wheels of strategic transport planning going. All excellently led by Joan and Ryan. The weak link in all of this? It was us actually. Right now all the publicists among you are thinking "this is a website where you meant to be showing how good you are. Why are saying this?" It's simple really. We were the weakest link, and we have no qualms about saying it. As much as you shout about your strengths, you must acknowledge your weaknesses. They show you who you are, and what you learn from these mistakes speaks more about you than going on about your strengths. We found it hard going. Leading a team was hard. The commute was hard. The circumstances were hard. Just putting your head down and getting on with it doesn't cut it when your head is in the firing line. We did not learn this quickly enough, and our own performance and that of the team suffered as a result. We never really recovered either, despite being given numerous opportunities to. We needed a new mindset to how we delivered our work, and we did not adapt quickly enough. You can't hide, you must lead. And leading is something that you can only learn the hard way. It took us until 6 months after we left Buckinghamshire to realise that. And to even to start learning from it. Whilst at the same time we were learning whole new, and even tougher lessons about setting up an entirely new company. Mobility Lab was formally incorporated in November 2018. We have run a whole host of seriously cool projects and events in the time that we have formally been in business. We even hired staff and a team of associates to help us out, and it nearly broke us. It turns out that wanting to put communities at the heart of transport policy? There's not much money in it. We set ourselves up to do great things to empower others, but in order to help out others you need to be able to support yourself. And we lost the first year of Mobility Lab because of this. There is no sugar-coating this. We nearly lost everything. That included the house and the family. Being in that situation completely re-wires your brain. At points we saw no way out. Every path through the woods was lined with ravenous wolves waiting to pounce when we slipped up. For a good 6 months everything spiralled downwards. No major peices of work. No sleep. No hope. Time to end it all, if you get what we mean. Those sorts of depths are hard to get out of. People fight these depths every day of their lives. Many of them never make it out of them. We cannot say for certain what really helped us out of those depths. Great friends and supporters helped. Winning work definitely helped. Actually having a rest also helped. So did the great people at the Natwest Accelerator in Milton Keynes, who really were great friends when we needed them to be, and whose advice we eventually listened to. Looking back on that time now gives us a strange feeling. Many of the troubles of the first year are still with us (we are working on them). In a way we are thankful that we got to experience it, as we deserved it for many stupid decisions. It was a necessary evil for us to experience. Even if for the best part of a year we have been unable to achieve what we wanted. We needed to experience it not only to face the brutal reality of the free market, but to completely change how we work as an organisation, and how we approach the projects that we do. In addition to learning brutal facts about how we do things, we learned brutal facts about others as well. We always knew that changing transport was going to be a hard task. There are certain truths that are accepted by our sector about how transport is, and certain nicities about how transport should be. This is a very important distinction to make, as it is something that blurred our thinking for a long time. And was at the heart of the mistakes that we made.

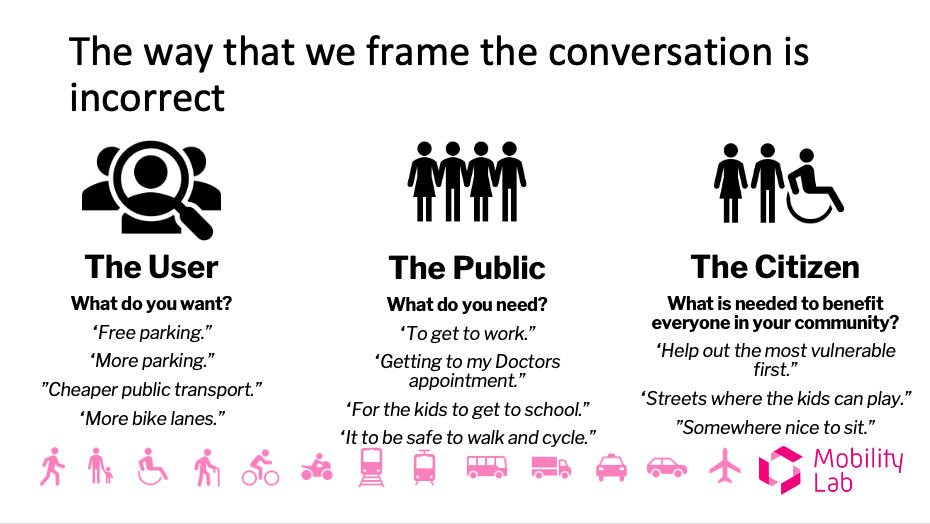

Things that the profession accepts as 'is' include efficiency, safety, economic performance, and reliability. All necessary, and things that we accept are important. The nicities include sustainability, access to services, even we daresay putting joy into people's lives. We have learned over the years that the nicities are as important to people as the things that we consider important as professionals. Occupying the space between the essentials and the nicities in this way is not an easy place to be. We thought it would be because, well, it made sense to us. We got lucky in the end. Projects came along to keep us afloat, and we have a small core of good friends that have helped us through the tough time. Now that we have, our purpose is clear for us, as well as what needs doing to make it all change. Because we never want to go back to that dark place again. And we want to lift people out of those same dark places. One transport scheme at a time. If you haven't checked out Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, or Part 5 of the history of Mobility Lab, then you should before reading on. All good things must come to an end. After the better part of a decade in public service, I got a random message. Alex Burrows, then of Transport for the West Midlands, messaged me through LinkedIn. "Followed you for a while. I like what you say. Fancy chatting about an opportunity?" was the simple message. At the time I was growing tired of the politics of local government. Not the actual politics you understand, the office politics. And ALL. THE. DAMN. PAPERWORK. For everything!! Having to fill out a 2 page form to buy a train ticket to a conference was the final straw I think (no such forms for driving, you see). So, why not? I thought. We met up at All Bar One on Midsummer Boulevard in Milton Keynes. The offer was a simple one. Alex was part of the Innovation Team at the newly-established Transport Systems Catapult, and wanted me to join. He liked the way that I thought, liked the stuff that I was sharing (I was sharing a lot on the impacts of new technology at the time), and wanted to know if I wanted to be at the start of something new. Later that week I went for an interview. Later on the day of the interview, I was offered a job. Within the week I had accepted, and within the month, a new professional life had started. But the same problems came back. The Transport Systems Catapult in its earliest days (I was the 30th ever employee) was an exciting place to be. We had been tasked by the UK Government, through InnovateUK, with a simple task. To accelerate the adoption of new technologies across the transport sector, and to create new jobs in the UK economy as a result of it. We had to set our own direction, and it was something that we went about doing with a religious zeal. My early work was relatively simple. Analysis of the transport technology market, and the supporting capabilities needed to make it a success. The Innovation Team was attempting to set the tempo of the whole company, so in addition to helping write the company strategy and undertake the supporting analysis (my job along with Alex Burrows and Ana Reynolds), we were running innovation competitions (Paul Blakeman and Ruth Dixon), undertaking capability analysis (Howard Farbrother) and running events. I will be honest. For a long time I was WAY out of my depth. I was learning new skills at the same time as working on projects to timelines that experienced professionals would have struggled with. The projects were really exciting, the team were all amazing, and whilst the company had its issues (for me to share more, you'll have to grab a beer with me), it was a fun and thrilling place to work. Yet there was a way that people spoke of the opportunity in transport that didn't sit well with me. It was all about the money, and user-centricity. That's it. That was the extent of the thinking. Early on in my time at the Catapult, I helped to come up with a figure for the global 'Intelligent Mobility' (a phrase that has meaning attached to it but means nothing) market - £900m. It was little better than an informed guess based on a literature review and some interviews. It was treated as though it was scripture. Everything became about that figure. The technological promised land would achieve this. Driverless cars were around the corner. We would make integrated ticketing a reality almost overnight. Smart cities would be rolled out within 5 years. Every utterance by a tech god was shared as though it was spoken from the lips of Christ himself. A completely user-centred transport system would somehow work and reduce congestion because of the Internet of Things. The loudest advocates of this technological utopia got the short shrift they deserved the second that they actually started speaking to the market they were meant to be serving. Local authorities had huge power but barely enough money to keep basic IT running. A lot of people used buses, actually. Integrated ticketing is impossible without re-writing legislation. And driving a car is really hard, so teaching a computer how to drive one is even harder. I don't wish to sound unfair here. Many of those people learned their lessons quickly, and those of us in the business who actually knew how transport runs and how to run transport businesses did speak up. But the most ardent promoters of the technical utopia didn't so much as not engage with reality. But they argued with it, insulted it, and stormed out of the room when it didn't do what they wanted it to do. We did some excellent work there that really started to change the mindset of many in the transport industry who were focussed purely on operations. A good example that I was not directly involved in was the UK Traveller Needs Study, where we undertook extensive consumer research to identify the needs of travellers and how they can be served by emerging transport technologies. Led by the excellent Phil Wockatz, it truly was a ground-breaking study, and one that I still see referenced to this day. But there is a big difference between user-centricity and citizen-centricity. I touched on this recently in a presentation that I did at UX:MK, but I have summarised this in a slide reproduced below. By considering user-centricity as the end game for mobility, you are framing what transport is about - and the surrounding conversation - in a completely different way. User centricity is individualistic. It is based upon what is valuable to people as individuals, and how you supply that in a manner that is profitable or at least the most economically advantageous. It meets both individual needs and wants, in a manner where over time, wants are considered to be needs. Citizen-centricity flips the whole approach on its head, which is critical for a commons such as transport. We already have a user-centred transport system. It's called a private car, and guess what? Trying to be user-centred is impossible without significant negative externalities. In the inevitable battle for space, time, and effort that takes place where user-centricity occurs, the strongest always prevail.

Citizen-centricity makes you think about the needs of others in communities and throughout society. Those who we don't think of usually when we make transport choices or develop strategies. You are not creating mobility systems around your needs, but around the needs of others. You set out to plan for people who are not like you. In transport planning, we boiled planning decisions down to vehicles, economic units, and occasionally excluded groups when we are required to do so by the Equalities Act. In transport technology, we boiled planning decisions down to market opportunity and use cases. Occasionally both used user personas, a method that is useful but can easily conflate wants with needs, not to mention that they are instantly forgotten once you start actually doing things. In fact, the other thing that both transport planners and transport technologists had in common was the hunger for more data from people. A relationship that is extremely one sided. Whenever I asked why new mobility providers and transport planners need more data, the response is usually "So we can make better decisions." As though if we just knew more about people, then we could help them make (what we think are) better decisions. Because they cannot be trusted to make the right ones on their own. I digress. Two years into the job, I felt as though I had come full circle. Tonnes of cool projects, but the same attitude to people. Treating them as a resource to mined, cattle to be herded, and above all for the decision making authority to be taken from them. And that's not counting the fact that we were not engaging people in a decent discussion about what the future of mobility means for them. We were about to launch huge technological experiments with new mobility technologies with a public who doesn't even know that it was taking place. The debate taking place was polluted with luddites and evangelists, with the public largely ignored. It was time to change the conversation. And that is where Mobility Lab really began to sprout wings. If you haven't checked out Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, or Part 4 of the history of Mobility Lab, then you should before reading on. It's easy to get distracted by the big, shiny things. Especially in the transport industry. You know what I mean. Ooh, a big new railway line. Ooh, a nice new motorway. Ooh, nice shiny driverless car. These are are the things that politicans (usually men, in a hard hat and hi-vis jacket) like to stand in front of. As though to say "look at what I did" despite not having even heard of the thing until that very morning. The things that fill the columns of the commenteriat, and we spend far too much time as professionals talking about. The things whose difference to people's lives are in no way related to the money spent on them, or the priority given to them. We should know. Our team has helped build infrastructure projects from multi-million bypasses to zebra crossings. Smaller is more meaningful and has a bigger impact on people everyday. They are better value for money, and achieve far more than big infrastructure. And a perfect example of this is a small building next to a motorway and a railway line. This is the story of Ridgmont station. For many years, our team members worked with the Marston Vale Community Rail Partnership. A partnership of local authorities, community groups, rail users, and the train operator who wanted to boost passenger numbers on the Marston Vale railway line between Bedford and Bletchley. A lot of this was doing basic work to promote the line in the community, and supporting station adoption groups. All very well received, and all popular. But we had eyes on another prize. In 2008, the Ridgmont Station Building stood disused. Next to the Bletchley-bound platform, and originally designed to be the home of the station master, it was...doing nothing. A monument to the glory days of railways. But with bags of potential. The Partnership wanted to realise this potential. What it wasn't going to do was bring the building back into its original use. The concept of a station house doubling up as a ticket office staffed by railway staff was long gone. That went with the Beeching cuts. Instead, the grand vision was for the building to become a true hub for the community. For months, we spend time kicking around ideas. Community shops probably wouldn't have the passing traffic to be viable. Nor was the building big enough for offices for small local businesses. The area was already awash with community halls as well. Eventually, we settled on a relatively simple idea. Downstairs, we would have a tea room in the former ladies waiting room, and a small heritage centre in the old ticket office. Upstairs, we would have some small offices for businesses in the old station master living quarters. We took our ideas to the parish councils and rail user group - they loved it. In fact, everyone loved the idea. Having stood derelict since the 1990s (we know it was that long because on a visit to the house, a copy of The Sun dated 1995 was found behind the ticket office counter). Network Rail also agreed to rent the building on a 99 year lease on a "peppercorn" rent of £1 per year. There was one problem. The £300,000 cost of the work. We had managed to secure £70,000 from the Railway Heritage Trust for the cost of repairs to the building. On one condition. We find another £30,000 from somewhere to fund the rest of it. We applied to lottery grants, the Landfill Communities Trust, and the Local Transport Plan budget. Nothing. This scheme that would have a genuine community benefit was going to fail over the price of a zebra crossing. We had almost no time to find it, or it was over. The update report to the Community Rail Partnership Steering Group made for sobering reporting. But on the train home, we got a call. It was the planning department at Central Bedfordshire Council. They had been going through the old planning agreements, and came across something very interesting. A local employment site had paid £32,000 towards "transport interchange" improvements at Ridgmont station. Improvements that were unspecified, and importantly the money had not been spent. And was just about to be handed back to the developer. "Have you got anything to spend it on?" they asked. "You know what, I might have just that." was the inevitable reply. This project was saved by a chance phone call. We worked out all the legals, and got letters of approval from the developer for a slight variation in the planning agreement. The money was transferred into the project account withon 30 days, and the Railway Heritage Trust funding was secured. From that moment, we never looked back. Today, the building has been open for close to 7 years. The Tea Rooms in the building have a 4.5 star rating on Tripadvisor, as does the Heritage Centre. A number of businesses have called the place home over the years, and community groups have held numerous meetings and informal get-togethers over the years. If you head there at any time there is always something going on. The place has a real buzz about it. Sitting in the tea rooms, and wandering the Heritage Centre, we can't help but reflect on the impact this scheme has had on people. Not just those who visit either. But the people who volunteer to help out at the Heritage Centre, and the new businesses established because this station building now has a purpose. A tangible purpose.

These are impacts that are not measured by traditional transport analysis. But they are as meaningful to people than what we traditionally measure. Perhaps even moreso. The opportunity to build connections between people, and to contribute towards something bigger than yourself. Does a bypass do that? Ridgmont Station Building often occupies our thoughts when we think about what transport should be, and what it often isn't. It should be about giving meaning in people's lives, and the opportunity for them to contribute to something more than just themselves. This is how our work generates impact. Just talking about public engagement is good and everything, but it doesn't generate any sort of impact. And if you want to demonstrate impact in terms of potential economic growth and journey time savings, there are already plenty of consultants who will do that for you. But if you want to create a social impact. Or to enable people to volunteer on projects or to create something more. To allow new businesses to start up in a manner that is demonstrable. To give a place for people to meet. To create more interactions between people. Then we can help you with that. What transport planners currently measure gets funding, and meets the requirements of HM Treasury. The reason why this is the best £30,000 we ever spent is because the impact of what we did was meaningful to people and it has had a lasting impact on people. Not convinced? Then take the train to Ridgmont. Have a cuppa and a wander around. Observe how people use what we helped to create. Then tell us that the bypass you are promoting, or that new railway line will have as meaningful an impact. If you haven't checked out Part 1, Part 2, or Part 3 of the history of Mobility Lab, then you should before reading on. An uncomfortable fact that you learn early in public engagement is that for most people, talking to the public is really hard. As social animals that comes as a bit of a shock. We are really good at establishing social circles, and co-operating has been critical to our survival. But engaging people in decisions is another matter. Throughout my life I have never been able to explain this. But once you realise it, you see it everywhere. The first time that I started seeing this was during the UK General Election of 2005. This was only my second as a registered voter. As a second year University student, my interest in my first election was non-existent. My second election made we wonder why we run them at all. I live in what is known in the UK as a safe seat. It has returned a Conservative MP in every election since 1932. The Conservative Party could put a pig with a blue tie up for the vote, and it would win. This is reflected in the nature of the political debate that takes place locally during the election. I have lived in this seat for five elections now, plus two referenda. In that time, I have seen one candidate canvassing for votes, and received a total of five leaflets through the door. At a time when there is meant to be a big debate taking place on the future of the nation, there is no invite to it. "But you have to educate yourself. It is your duty as a citizen to be informed before voting" more than one person has said to me. But if candidates cannot be bothered to put the effort in to secure my vote, why should I vote for them? When they clearly don't care about coming to get my vote? Over the years, the direction of my vote has been determined by a simple rule. If you have made the effort, I will think about voting for you. If you can't be bothered, I won't vote for you even if I like your policies. The same thing applies to public engagement. If you can't be bothered to make the effort to engage them, why should you expect more people to engage? You have no devine right to their attention. People should not expected to care about what you are doing, and how important it is to them. You should not expect people to educate themselves. If you don't make the effort, don't complain that others do not. This is partly why public engagement is done so badly most of the time. Good public engagement takes time and effort. Not to plan and to do. But to convince people that you care, and you are engaging on their terms. Trying to engage people on my terms is a mistake that I often made. Once a month for two years, I stood at a stand at Leighton Buzzard railway station trying to convince people to try out the bus or local cycle routes to the station. It went about as well as you would think. Most people ignore you. Then some take a leaflet just to get you off their back. Perhaps one or two thought about taking the bus. My failure to convince people I put down to not being there enough, and not puttng the hours in. I wasn't selling enough. I convinced myself it was a numbers game. Just talk to more people over more mornings and evenings. I was wrong. That revelation came one dark December evening in 2010. I was on my fifth shift promoting sustainable travel at the station of the week. It had been a quiet night, and I had been routinely ignored by exhausted commuters heading home after a long day at work. Then Claire (not her real name) walked in. As tired and as stressed as the rest of them. More out of hope than anything, I asked her whether she was interested in finding out about different options for getting to and from the station. "It would save the hassle of getting a taxi" I said as a throw away comment. "Ahh...why not?" she said in response. The next 30 minutes was not spent talking about buses, bikes, and detailed journey planning. But with Claire sharing with me her life. The job with the long hours, trying to balance a home life alongside this, and the sweet relief of the Americano served by the station cafe in the morning. The cafe owner may have been in earshot at that point. In part this seemed like therapy for her. I didn't mind, and not because it had been a slow night. Seeing the visible relief on her face at sharing her worries with someone was enough for me. Bus timetables and discounted fares suddenly lose their importance during times like that. I had completely forgotten that I had even given her a bike map. I wasn't sure if any of what I was doing was helping. There was little change in facial expression or demeanour, and all I was saying was "ok," "uh-huh," and "I understand" every few minutes. But we parted on good terms. Six months later, I was working Leighton Buzzard again. Yet another bust of a morning. Out of the blue, Claire emerged from the coffee shop, Americano in hand (I assume it was an Americano anyway). We had a few minutes until her train arrived, so I asked how things were. Same old, same old apparently. But she had started cycling to the station. She noticed the bike map in her handbag a couple days after I spoke to her, and it reminded her of our chat. She took some adult cycle training lessons, and bought herself a new bike. And she was now riding to the station most days. What's more, she had talked to some of her friends, and they had started riding at the weekends. All from a chat and bike map, and sheer blind luck you may assume. But you would assume wrong. Engaging with people is not a numbers game. Nor is it about trying to convince people. It is about showing people that you give a damn about them, their lives, and what is important to them. It is about listening - the most important part of engagement. And I mean really listening to people. The next time that you are thinking about public engagement, try this. Instead of listing out what you want to achieve from your next community engagement activities, list what you want others to achieve from it. Should they engage with you to be informed? To have an impact on what you are doing? Or to get their worries off their chest? And then how would you plan your engagement differently?

Simple questions like this change public engagement for the better. They are questions that we almost never ask in favour of our own objectives. Time to start asking them. If you haven't read Part One and Part Two of the story behind Mobility Lab, then I recommend that you do so before proceeding on. Also, just to note that the names in this post have been anonymised, and the pictures are random ones I found off the internet. Sadly, digital cameras were not widespread when I did these engagement events! "Why should I give you my view? You don't care. You just want to tick a box." "Ok, here's my view. The Council are useless and you should all be sacked. I've reported the p****s 5 times and nothing has been done about them." "Look, we just don't want the gyppos around here. Just blow up their caravans and be done with it." How do you overcome that level of vitriol in a public engagement exercise? Can you? When there is an out-group that is so hated, any form of public dialogue exposes some of the very worst in people. Not long after the disaster of my local transport plan consultation, I had the opportunity to observe a consultation exercise being run by Mid Bedfordshire District Council. This was the first of two such exercises on planning for Gypsy and Traveller sites across the district. The Council was required to identify suitable locations for new sites and pitches that could cater for their needs. This consultation was intended to share the first ideas. I was along for the ride as the transport expert. For those who are not aware of the status of Gypsies and Travellers in the UK, the attitudes to them amongst the majority of the public have been described as the last acceptable form of racism. The level of the debate that took place was exactly what I expected. Everyone was invited to have their say. Add in a spot of hatred, and what resulted was something worse. Lots of comments that were vile and contributed nothing. The planning officers were understandably anxious about planning the next round of events. They approached it with a management ethos. Lets just manage the comments. People won't like what we have to say, so lets take the hit and get it over with. I wasn't having any of it. 'Just managing' wouldn't happen. I started this turn around of the events by stating a simple observation: in all of the engagement exercises that we did, not one gyspy or traveller attended. Not. One. "We are creating a policy to benefit them, and they are not having a say in it. For what other policy would that be acceptable?" I asked during a meeting to plan the next round. "Why are we not talking to them?" We were guilty of much of the same prejudice that we had sworn as public policy makers to never let influence our decision making. We simply didn't know how to engage with people we were creating policies for. Worse than that, other policies actively worked against us. For example, ff we wanted to go onto a traveller site, our risk assessments stated that the only safe course of action (and thus the only thing covered by our insurance) was to have a Police escort onto the site. This made my plan seem mad. Simply talking to them was mad. That's mad. The plan that we eventually came up with was simple. We would first bring on someone who knew about all this better than the rest of us. So Simon came on board (I won't share his surname, as I know that he has had threats against him from supposedly 'decent' people). He advises planners and local authorities across the UK on gypsy and traveller issues. He knew how to get into the communities, and he knew them far better than we did. He first spent a day with us, downloading everything he knew. That the crime rate of those groups is no different to the national average, but they are more likely to be victims of crime and to be arrested than other ethnic groups. About their family structures, cultural norms and traditions. We learned so much in just 8 hours. His next job was to then set up meetings between ourselves and members of the gypsy and traveller community. To allow us to ask questions of what their needs are, and what they would like from the policy. We argued the hell out of this with our risk assessment teams. We eventually got a compromise. There would be at least 3 members of the team present, and no all-women groups on our side. Simon should also be present if possible. I personally attended two such meetings. Not only were the families warm and welcoming, but in 30 minutes with them I learned more about their site needs than I could have imagined. They wanted some extra pitches for visitors. They wanted good access to the main roads, and connections to electricity and water. They wanted the Council to take swift action against people who they knew would be trouble makers, and not against everyone in their community. They also told us that having a mix of types of site (some for permanent residents, others for transient populations) was critical. Naturally, ensuring the sites were safe and defendable was a major thing for them too. The second action we then took was more bold. For each of the planned public meetings, we wanted them to run differently. No longer would someone from the planning department presenting, and then opening up to questions / hate from the audience. The planners would set out why we are doing this. Then Simon would set out the facts about gypsies and travellers. Finally, and most boldly, we invited a member of the local travelling community to present their side of the story. The final part took a lot of convincing on all sides. You are essentially asking for a member of a community who is widely hated to tell everyone why they need help. It is a huge target on their head. For us, putting this to Councillors was almost impossible. "Why should those scum get to have a say?" said a Councillor who shall not be named. We stuck at it, and through sheer bloody-mindedness on our side, eventually the objections relented. On the advice that the local police officers be in attendance at each event. Some weeks later, our first event took place at Maulden Village Hall. An evening meeting. We knew from the Parish Council that a local action group had been established, and was planning to turn up en masse at the event. We also knew from Simon that 5 people from the local travelling community would be there. Councillor Shadbolt, our chairperson for the evening, joked to me that he had his riot gear in the boot of his car. At least I think it was a joke. As the room began to fill up, and with 10 minutes to go before we kicked off the meeting, we got into a huddle. As council officers, we must be neutral and sympathetic. Councillor Shadbolt needed to have a firm hand on the wheel. Simon needed to be authoritative and clear. Sean, the member of the local travelling community who would be speaking, just needed to be himself. Our game plan was a simple one. Take the sting out of the evening first, and then build empathy from there with a reasonable debate. 100 people were crammed into a small village hall. There were signs saying "No more travellers" and "Evict gyppo scum." Everyone was glaring at the 5 men who volunteered to put their needs forward. "This will get ugly" I thought. I thought wrong. The people there gave Simon the hardest time. There were howls of derision as he shared the facts that he shared with us. Councillor Shadbolt kept a firm lid on things. But then Sean began to speak. He told everyone present about his family. About how his mother, from when he was young, instilled in him a strong work ethic and family-first attitude. About how much he cared for his 2 young daughters, and how frightened he was for their future. Throughout his own life he had been randomly assaulted in the street more times than he cared to remember. His brother had been stabbed by a random teenager who stated to the police that all he wanted to do was "murder a gyppo." Luckily he recovered. He faced accusing looks all the time, and whenever something bad had happened in the local area, he knew the police would come knocking. In all the times he had been assaulted, the police only took a statement once. He worked hard. He paid his taxes. He spent money in local shops, and when people in his community got out of line he took action. He hated the worst people in his community as much as everyone else. And when he was asked why this policy was important, he answer was simple. "It gives me a home to defend, and to call my own. I don't have that." The room was stunned into silence. At the end of the evening, I mixed in with the people who were there. They all remarked on Seans speech, and how it challenged how they saw the travelling community. For most of them, it was the first time they had actually heard from a member of the travelling community. "I can't imagine what it must be like to live with the thought that at any moment you could be assaulted" said one. "Look, I still don't like the plans, but credit to that Sean bloke. Perhaps it is time we turned down the rhetoric a bit" said another. Simon was talking to Sean throughout. I learned later that Sean and his 4 friends felt really grateful for having the chance to have their say. And that they felt like someone was listening to them for once. We had achieved something quite extraordinary. By focussing our efforts on the people who really mattered, putting them and their needs at the centre, and challenging the mob mentality, we had made the engagement exercise more meaningful to everyone. This wasn't just through more positive public meetings. We spoke to 30 travelling families over 12 weeks, and made changes to our policies, including design and service standards for new traveller sites. We had letters from grateful members of the public thanking us for some excellent community meetings, and Councillors congratulated us on a great job. The majority of the comments we received were still objections. But hey, baby steps and all. This was how engagement should be. Put the people you are trying to help front and centre. You should empower them, not ask them for their view. You should really focus on who you want to talk to, and do everything in your power to make it about them.

This often involves knocking down barriers, blowing up rules, and challenging cultural norms. I can safely say that what we cut our teeth on was probably the hardest group imaginable because of the barriers that misconceptions of that group have created. We fought long, hard, frustrating battles on their behalf. Unseen. Good public engagement is not pretty, and too often public engagement gets tied up in methodology. Most of it is shitty work where you have to fight long, lonely battles for what is right, because you have the power to do so. Throughout a long summer, we fought those battles, and we won them. And our engagement was all the better for it. If you haven't read the first part of the story behind Mobility Lab, we suggest that you check it out before reading on. John was right you know. Consultation really was a basic process. For about 6 months I kept up the gig in planning. House extension, after house extension, after house extension. The same routine day in, day out. Send the letters to the highway authority and the parish council. Go out and put the site notice up. No old ladies this time. Or any time. The most that I got out of consultation was angry letters from neighbours who clearly don't get on with one another, bringing in every beef apart from planning issues. The woman who said that their neighbours couldn't have planning permission because "it would encourage ne'er do wells and single mothers to hang out at their house more" was a personal favourite. The name that she gave was H. Bucket. I swear that is true. Eventually, I changed jobs, and the first significant shift of my career took place. I took on the role of Assistant Transport Officer at Bedfordshire County Council, based at what was then called County Hall in Bedford. A monolithic, curved, massive 'screw you old town character' of a building so favoured during the late 1960s and early 1970s in architects departments in local authorities at the time. Famously built to have 7 floors, but only had 6 completed as the entire building began to sink into the ground was the 6th floor was build. It was the first time I got to work in what felt like a proper team. The team leader was Glenn, an incredibly bright and easy-going team leader who had forgotten more about transport policy making than the rest of the Council knew. His finger was in every pie, from the Bedford Western Bypass to reviews of passenger transport. He knew what was happening, all the time, regardless of how left-field the question was. Then there was Mel and Kim. The life blood of the team, the soul of the party, and whose reputation as a fearsome two-some was both unwarranted and completely true at the same time. Both locals (though like true Bedfordians - born elsewhere), they knew the County like the back of their hands, and how to handle almost any issue that was thrown at the team. They were incredibly supportive of all of what we did right from the start. Did I say we? I started with someone else - Sarah. When someone introduces themselves as a former police officer it is meant as an ice breaker. Although a risky one. But she did not come across as you would expect a former officer would. Very kind and considerate, whilst I struggled in the first few weeks she took to the job like a duck to water. It really set the tone for the rest of our time there. Then we had Dave and Ian working on the technical side. I got on well with both of them. Ian because he is a Manchester United fan, and Dave because we lived in the same village. But generally our work paths did not cross. Apart from making the tea and saying hello in the morning, our work did not cross for many years. The big piece of work that the team was working on at the time was Local Transport Plan 2 (LTP2_. With a deadline that the team had to meet to get government funding, and a lot of work that needed doing to improve on the Draft LTP2 (it was scored as poor by the Department for Transport), myself and Sarah were given a choice, Do accessibility planning, or do the consultation. Take a wild guess what I chose. My task was simple. I had to plan for an 8 week consultation period on the Final LTP2, and improve on the disasterous score of poor from the Draft LTP2. We had JMP Consultants on board, and about 2 months to plan it. So we got cracking on it. The first part was review the comments from DfT on LTP2. "No evidence of meaningful consultation." Great, thanks DfT. That's really helpful. Little was I to know that I would be spending a lot of time in the rest of my career saying exactly the same thing. In a way, it was liberating. As whatever we did could only be better than what was done for the Draft LTP2. So we decided to keep our plan simple, and hit as many communities as we could throughout the 8 weeks. There was no science to it, no deliberate thought given to how we specifically target individual groups, nothing. Just hit as many people as we could. It was a car crash. We held public exhibitions in libraries all over the County. We ran evening workshops in community halls across the authority, inviting members of the community to come and discuss transport and give their views. We promoted the consultation in the local paper for weeks, and ran stories and press releases on what we were doing. The total responses from the public? 23. All that taxpayer money. All that time. All that promotion. For 23 comments from members of the public. Of course we received comments from key stakeholder groups. We would have done so even if we did nothing. So the consultation was a complete bust. We did turn it around though through just providing evidence in LTP2 of how individual comments from specific stakeholders informed or aligned with our policy. A quote here, a finding from a survey there. All boosted the score from poor to good. The consultation was still a disaster though. It was a few months after we submitted the Final LTP2 to Government that we finally got to de-brief on the whole experience and what went wrong. The answer was so simple that it almost felt wrong. After talking for hours about the people who we spoke to, the reach of the press releases, the letters sent out, the quality of the consultation materials and the supporting website, we reached this conclusion.

By trying to involve everyone, we hit no-one. It is tempting to think that by trying to involve everybody then you are giving everyone a fair say. Everyone has an equal opportunity to be engaged in the process, and everyone will be hit with the message that the consultation is happening and that they should have their say. It seems fair, equitable, and objective. But that is completely the wrong way to think about it. Not only will most people actively ignore you, but by refusing to target people you are unwittingly being unfair and inequitable. The people who have the most to say about transport are the ones that have the greatest difficulty using it. You are relying on them to get out of their homes, come and see you, and comment passively on plans and policies that make little sense to them. We did not go to them, in any sense. We just got closer to them than County Hall is. We did not take the essential first stage in community engagement. You must go to where the people who you want to engage with are, and engage them on their terms. It was a mistake that I would not be repeating again any time soon. Next time, I would get it right. And it wasn't long before I got the opportunity to do so again. |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed