|

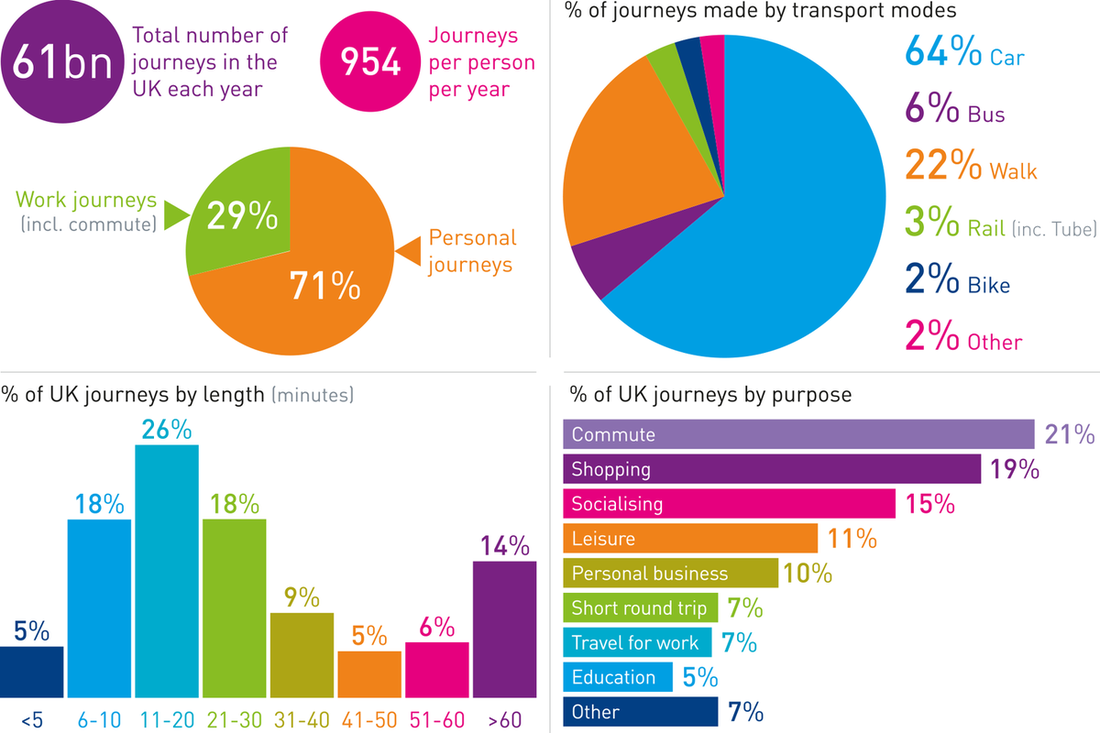

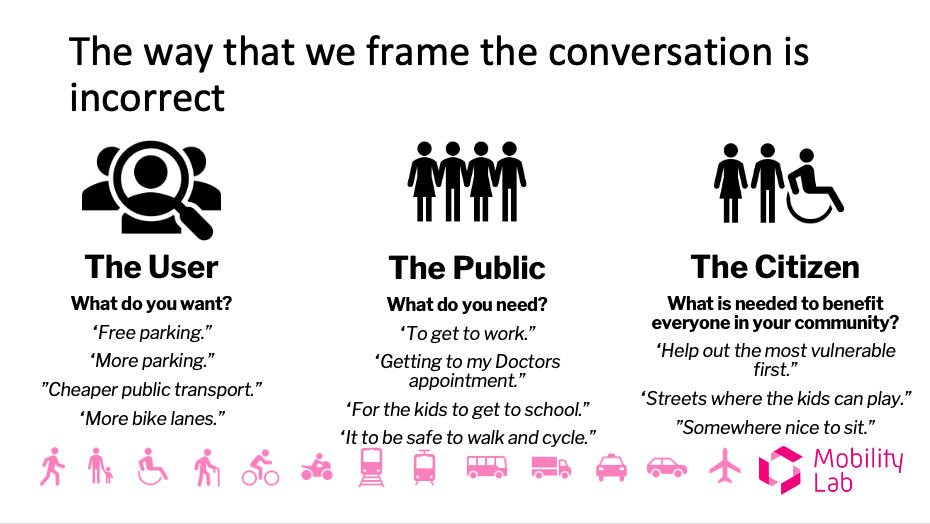

If you haven't checked out Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, or Part 5 of the history of Mobility Lab, then you should before reading on. All good things must come to an end. After the better part of a decade in public service, I got a random message. Alex Burrows, then of Transport for the West Midlands, messaged me through LinkedIn. "Followed you for a while. I like what you say. Fancy chatting about an opportunity?" was the simple message. At the time I was growing tired of the politics of local government. Not the actual politics you understand, the office politics. And ALL. THE. DAMN. PAPERWORK. For everything!! Having to fill out a 2 page form to buy a train ticket to a conference was the final straw I think (no such forms for driving, you see). So, why not? I thought. We met up at All Bar One on Midsummer Boulevard in Milton Keynes. The offer was a simple one. Alex was part of the Innovation Team at the newly-established Transport Systems Catapult, and wanted me to join. He liked the way that I thought, liked the stuff that I was sharing (I was sharing a lot on the impacts of new technology at the time), and wanted to know if I wanted to be at the start of something new. Later that week I went for an interview. Later on the day of the interview, I was offered a job. Within the week I had accepted, and within the month, a new professional life had started. But the same problems came back. The Transport Systems Catapult in its earliest days (I was the 30th ever employee) was an exciting place to be. We had been tasked by the UK Government, through InnovateUK, with a simple task. To accelerate the adoption of new technologies across the transport sector, and to create new jobs in the UK economy as a result of it. We had to set our own direction, and it was something that we went about doing with a religious zeal. My early work was relatively simple. Analysis of the transport technology market, and the supporting capabilities needed to make it a success. The Innovation Team was attempting to set the tempo of the whole company, so in addition to helping write the company strategy and undertake the supporting analysis (my job along with Alex Burrows and Ana Reynolds), we were running innovation competitions (Paul Blakeman and Ruth Dixon), undertaking capability analysis (Howard Farbrother) and running events. I will be honest. For a long time I was WAY out of my depth. I was learning new skills at the same time as working on projects to timelines that experienced professionals would have struggled with. The projects were really exciting, the team were all amazing, and whilst the company had its issues (for me to share more, you'll have to grab a beer with me), it was a fun and thrilling place to work. Yet there was a way that people spoke of the opportunity in transport that didn't sit well with me. It was all about the money, and user-centricity. That's it. That was the extent of the thinking. Early on in my time at the Catapult, I helped to come up with a figure for the global 'Intelligent Mobility' (a phrase that has meaning attached to it but means nothing) market - £900m. It was little better than an informed guess based on a literature review and some interviews. It was treated as though it was scripture. Everything became about that figure. The technological promised land would achieve this. Driverless cars were around the corner. We would make integrated ticketing a reality almost overnight. Smart cities would be rolled out within 5 years. Every utterance by a tech god was shared as though it was spoken from the lips of Christ himself. A completely user-centred transport system would somehow work and reduce congestion because of the Internet of Things. The loudest advocates of this technological utopia got the short shrift they deserved the second that they actually started speaking to the market they were meant to be serving. Local authorities had huge power but barely enough money to keep basic IT running. A lot of people used buses, actually. Integrated ticketing is impossible without re-writing legislation. And driving a car is really hard, so teaching a computer how to drive one is even harder. I don't wish to sound unfair here. Many of those people learned their lessons quickly, and those of us in the business who actually knew how transport runs and how to run transport businesses did speak up. But the most ardent promoters of the technical utopia didn't so much as not engage with reality. But they argued with it, insulted it, and stormed out of the room when it didn't do what they wanted it to do. We did some excellent work there that really started to change the mindset of many in the transport industry who were focussed purely on operations. A good example that I was not directly involved in was the UK Traveller Needs Study, where we undertook extensive consumer research to identify the needs of travellers and how they can be served by emerging transport technologies. Led by the excellent Phil Wockatz, it truly was a ground-breaking study, and one that I still see referenced to this day. But there is a big difference between user-centricity and citizen-centricity. I touched on this recently in a presentation that I did at UX:MK, but I have summarised this in a slide reproduced below. By considering user-centricity as the end game for mobility, you are framing what transport is about - and the surrounding conversation - in a completely different way. User centricity is individualistic. It is based upon what is valuable to people as individuals, and how you supply that in a manner that is profitable or at least the most economically advantageous. It meets both individual needs and wants, in a manner where over time, wants are considered to be needs. Citizen-centricity flips the whole approach on its head, which is critical for a commons such as transport. We already have a user-centred transport system. It's called a private car, and guess what? Trying to be user-centred is impossible without significant negative externalities. In the inevitable battle for space, time, and effort that takes place where user-centricity occurs, the strongest always prevail.

Citizen-centricity makes you think about the needs of others in communities and throughout society. Those who we don't think of usually when we make transport choices or develop strategies. You are not creating mobility systems around your needs, but around the needs of others. You set out to plan for people who are not like you. In transport planning, we boiled planning decisions down to vehicles, economic units, and occasionally excluded groups when we are required to do so by the Equalities Act. In transport technology, we boiled planning decisions down to market opportunity and use cases. Occasionally both used user personas, a method that is useful but can easily conflate wants with needs, not to mention that they are instantly forgotten once you start actually doing things. In fact, the other thing that both transport planners and transport technologists had in common was the hunger for more data from people. A relationship that is extremely one sided. Whenever I asked why new mobility providers and transport planners need more data, the response is usually "So we can make better decisions." As though if we just knew more about people, then we could help them make (what we think are) better decisions. Because they cannot be trusted to make the right ones on their own. I digress. Two years into the job, I felt as though I had come full circle. Tonnes of cool projects, but the same attitude to people. Treating them as a resource to mined, cattle to be herded, and above all for the decision making authority to be taken from them. And that's not counting the fact that we were not engaging people in a decent discussion about what the future of mobility means for them. We were about to launch huge technological experiments with new mobility technologies with a public who doesn't even know that it was taking place. The debate taking place was polluted with luddites and evangelists, with the public largely ignored. It was time to change the conversation. And that is where Mobility Lab really began to sprout wings.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed